Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Emotions as Discrete “Types”

- Why Would Emotions Influence Thought in the First Place?

- Illustrating How Emotions Shape the Way People Think

- Why Emotion-Cognition Dynamics Matter in Marketing

Introduction

In several posts, we have done our best to organize an evidence-based view on the role that emotions can be expected to play in life science marketing, along with an overview of research that shows the types of cognitive and behavioral effects that specific emotions have. We also made the case that, in most healthcare contexts, we are well-served in examining the effects of emotions on what we call “upstream” drivers of behavior change – those that are related to dynamics like thinking, beliefs and attitudes – rather than expecting evoked emotions to lead to immediate behavior change. And finally, we made the case that self-reported measures of emotion (of various stripes and formats) are probably better for measuring durable emotional characteristics and individual differences, such as tendency toward anxiety or a tendency toward positivity, than they are for measuring the impact of emotional responses elicited through marketing or persuasive communication.

Now we want to illustrate the specific kinds of effects that different types of evoked emotions have on various types of cognition – literally how people think differently when they are in various emotional states. Not only is this interesting scientifically, but it also has implications for business practices. Specifically, this area of science speaks to:

- The need to consider how we hope to encourage customers to think differently

- The need for thoughtful planning as to the precise types of emotions we want to evoke in our content to set up the best chances of those cognitive effects

- The need for reasonably specific and sensitive ways of measuring the emotions we DO evoke when we test our content

- And the need for thoughtful measurement and evaluation of the pre-post changes in customer mindset that result from our efforts

Naturally, there are plenty of limitations to what the accumulated science can tell us, but we now have enough information to support serious conversations about using emotions with some precision in the context of life science marketing. Given how much earnest focus goes into customer emotions in our industry, we feel that evidence-driven conversations are worth having.

Emotions as Distinct “Types”

In our post entitled, “Accepting the Limitations of Self-Report in the Measurement of Emotion”, we summarized what we see as some of the most practical and fascinating aggregated learnings from the science of emotion. We are going to provide a quick recap here, and then overlay some additional data, that pertains specifically to the impact of emotion on different thinking processes.

The first thing that we want to make the case for is that, for practical purposes, marketers and insights professionals are probably better off thinking of differences in emotion as being categorical and distinct. This means we are coming down on the side of the concept of what scientists call discrete emotions. That means, for example, that anger is distinct from guilt, sadness is distinct from anxiety, and jealousy is distinct from joy. You get the picture. Many of us who have been through an undergraduate psychology 101 course, will probably remember learning about Paul Ekman’s now famous work on the universality of basic recognizable facial expressions. Still debated, this work has since led to an impressive diversity of supporting research. At a minimum, we know that emotional experiences are easily recognized by other humans and conceptualized as distinct both in our own subjective experiences and in our understanding of others’ emotions. More recent neuroimaging suggests distinct brain activity signatures emerging when people interpret stimuli such as images of facial expressions or emotion-appropriate voice tones (a digestible summary of this neuroscience work can be found in Nummenmaa & Saarimäki, 2019). Finally, evolutionary psychology has helped researchers to think about and study emotions from the standpoint of the adaptive benefits they might produce. From this perspective, it makes sense that we would perceive differences in the feeling of anger vs. sadness (for example), because they evolved to drive different kinds of outcomes in the way we interact with our environments (Cosmides & Tooby, 2000; Lench, Tibbett & Bench, 2016).

But there is a much more practical reason to think of emotions as discrete entities. Extensive research on how elicitation of discrete emotion relates to downstream consequences strongly supports the idea of emotions as distinct from one another. In the aggregate, this work has produced a handful of strong conclusions related to our use of emotions in marketing.

- First, it finds strong evidence that marketing-adjacent content, such as images, narratives, film vignettes and personal recollections, can reliably produce distinct emotional states (see Lench et al, 2011), such as anger, fear, and happiness.

- Those elicited states have predictable results in terms of changes in cognition, attitude, intention, and behavior – what we have come to refer to as “outcome signatures” (Lench et al, 2011; Angie et al, 2011). What this means is that there is strong evidence that distinct, elicited emotions produce different levels of effect across a range of marketing-relevant outcomes.

- The effects of emotions are not just varied, but they can also be subtle. This is a key reason why having sensitive measures of the effects of emotions is important in the context of customer research.

For readers interested in learning about the counter-argument to the discrete emotions perspective, please see our Sidebar in the Appendix to this document. With these insights as a foundation, we will now turn to a more nuanced discussion about exactly how the emotions shape how customers think.

Why Would Emotion Shape Thought in the First Place?

To answer this question, let’s start by taking a practical lens on emotions. For me, the most useful way to conceptualize individual emotions is from a situational perspective – that is, to literally ask “Under what conditions would this emotion occur?” Let’s look at two examples, which I’ve lifted from a thoughtful paper by Lench et al (2016).

- Sadness: Arises when our access to a goal or resource is cut off, usually permanently or indefinitely.

- Anger: Arises when our access to a goal or resource is obstructed or delayed by some obstacle, normally something that is at least potentially removable.

It’s worth appreciating both how generalizable these situational definitions are (e.g., you could see them applying to a range of physical and social resources) and how such a seemingly subtle difference in the arrangement of external situations can produce profoundly different responses. Think of your own experience of anger or sadness and see how it aligns to the definitions provided above.

With these definitions in mind, we can ask ourselves another important question: “What is the value of having the emotion that arises in that specific circumstance?” This is where we can begin to see how downstream changes in cognition that arise from emotional experience might have value. In the case of sadness, we probably expect thoughts to dwell on what has been lost (as indeed they do), which may not have a ton of benefit; however, there is also evidence that sadness results in cognitions oriented toward mitigation of the lost resource, re-appraisal of available resources and planning for different behaviors in the future (including consideration of how to prevent similar losses in the future). In this sense, sadness activates rationality – that is, deliberate, careful thinking, or what people might glibly refer to as “System 2” engagement. When a goal is no longer attainable, the adaptive response is to learn as much as possible from the experience to minimize the risk of a similar loss in the future. In terms of cognition, anger is almost opposite to sadness. It activates more heuristic processing of information, impedes introspection and narrows focus of attention onto goal-relevant information. Remember that, with anger, there is still a chance of achieving one’s goal, so this laser-focus and discarding of peripheral information makes sense. Angry people are activated to work around (or through) their problem, while sad people are planning to mitigate future situations. These are interesting speculations, but the question is, do they hold up when studied experimentally?

Illustrating How Emotions Shape Peoples’ Thinking

The aforementioned meta-analysis by Lench et al (2011) showed clear differences in the raw magnitude of effects on cognition (compared with other outcomes) across four major emotion categories. But we want to be more precise and see if we can understand qualitatively how different types of thought are shaped by different emotions. We’ll look at five major components of thinking, each of which has important implications for marketers.

- Attention: Where focus settles among a range of competing stimuli

- Interpretation: Processes related to how customers extract the (intended) meaning of content, particularly if meaning is ambiguous

- Judgment: Processes related to the evaluation of object qualities based on evidence and estimation of the likelihood of specific events

- Decision-Making: Processes related to selecting from among alternatives and prioritization of information during the selection process

- Reasoning: Drawing conclusions about how the world works and making specific inferences from information

The literature on these subjects is not as organized as we might prefer, so we’ll be drawing from disparate sources here.

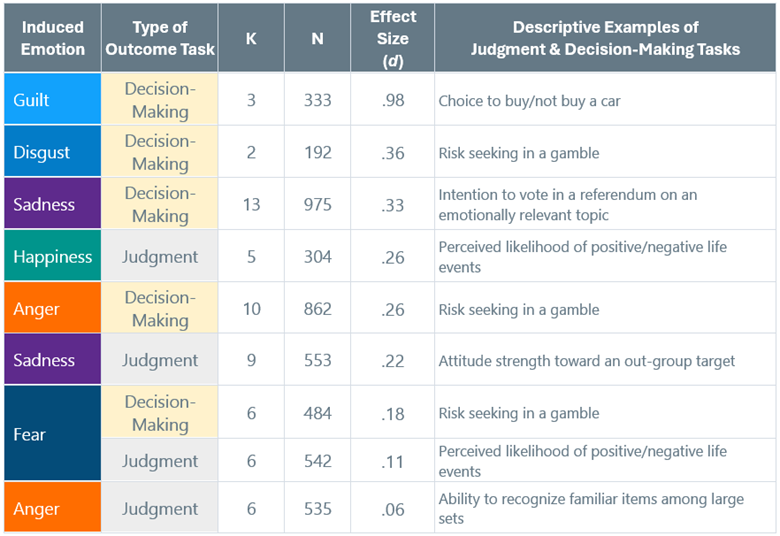

We’ll start with another useful meta-analysis by Angie et al (2011), which summarized experimental studies on the role emotions play in judgment and decision-making tasks. As noted above, the term judgment usually reflects some kind of appraisal of quality, value or likelihood based on a stimulus or scenario. Decision-making usually refers to the process of selecting between two or more options based on some valuation process. These two aspects of cognition are very commonly paired in cognitive science (see, for example, Newell et al, 2022 or consult any cognitive psychology text). In the table below, we’ve listed the induced emotion, the number of studies and total sample size, the obtained effect size and a simple set of examples for different types of judgment and decision-making tasks, just to give a flavor of the distinction.

Table 1. Differences in Judgment and Decision-Making Task Performance When Specific Emotions are Invoked (Compared with Control Groups)

As you can see, the effect sizes vary substantially between task-types and between emotions. For example, we can see immediately that, on average, anger manipulations do not seem to alter judgment tasks much at all, but they have a substantive effect on decision-making. For another, both guilt and disgust seem to have very large effects on decision-making. This aligns with arguments made by prominent evolutionary psychologists, who maintain that emotions serve as override systems that focus coordination of attention, stimulus interpretation and response in distinct ways (see, e.g., Sznycer et al, 2017; Cosmides & Tooby, 2000). And overall, it appears that judgment is less influenced by induced emotions than decision-making irrespective of the emotion in question. However, it is also possible that judgment tasks can be measured on a more fine-grained basis compared with mostly binary decision-making tasks.

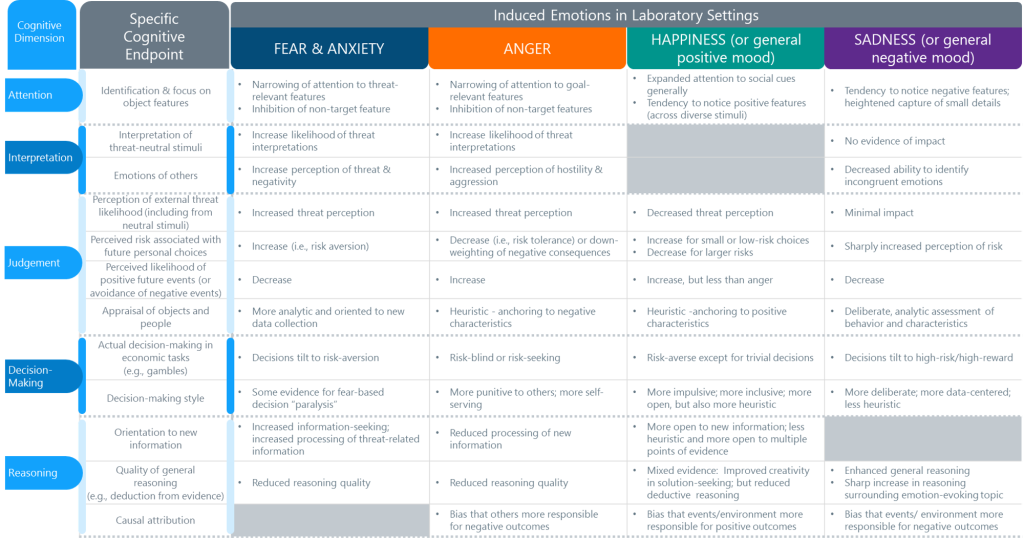

The Angie et al analysis is a step up in precision compared with the Lench et al data, in that it shows that effect sizes differ systematically for types of thinking crossed with types of emotions. Certainly, judgment and decision-making represent two of the more critical outcomes that we want to shape with our marketing content, but nevertheless, these findings still feel like blunt instruments. To take this a step further, we pulled together a synthesis of the accumulated evidence for how specific emotions explicitly influence the five components of cognition that we mentioned earlier. To do this, we examined a range of different sources, including qualitative summaries, book chapters, individual experiments, and meta-analyses. Because emotions are so diverse and numerous, it would be too space-consuming to create a map of all of them, so for this assessment, we follow the orientation of Blanchett and Richards’ (2010) literature synthesis and focus on those emotions that have been studied the most: Fear/Anxiety, Anger, Happiness (which we merge with general positive moods) and Sadness (which we merge with negative moods).

The available data are summarized in Table 2 below. If cells are greyed-out, it simply means that we have yet to find satisfactory direct experimental evidence for a given emotion-cognition relationship. Readers might naturally object that we have selected too-narrow a range of emotions, and that important topics like Hope, Gratitude, Disgust and Pride are excluded. As more evidence emerges, we may revisit this list, because we agree that a more comprehensive understanding of emotion-cognition dynamics would be beneficial to marketers.

Table 2. Differences in Cognitive Process as a Function of Induced Emotion Type in Experimental Settings

There’s a lot here, so we think it is worth boiling down some of the trends. In most cases, I find these effects to be reasonably coherent, with several real surprises.1

- THREAT CONSUMES COGNITIVE BANDWIDTH

- On balance, inducing emotions that relate to threatened resources (i.e., fear and anger), we see a heightening of emotion-related cognition. This translates to narrowing of attention toward the threatening object or situation and can also lead to information searching that confirms the interpretation of threat.

- HAPPINESS YIELDS BROADER ATTENTION, BUT SAFER CHOICES

- Happiness or induced positive feelings make people less narrow in their judgment, more charitable in their appraisals, more creative in their reasoning and more positive about futures and future risks.

- However, contrary to my assumption, happiness generally leads people to make less risky choices. Researchers reason that people generally want to try to maintain their positive feeling, hence taking a risk might expose you to negative outcomes that would break up your positive vibe.

- SADNESS YIELDS MORE RATIONALITY, BUT ALSO MORE PESSIMISM

- Interestingly, sadness appears (mostly) to serve as a rationality primer. Sad people tend to be more accurate in their evaluations – looking at a broader range of factors and features. They are more likely to be persuaded by data and more tuned-in to small details.

- At the same time, they tend to be more pessimistic in their interpretations of situations and others, and they tend to assume that future outcomes will be negative.

- For another example, I find it illuminating to know that people who are sad tend to be more likely to reach correct conclusions in reasoning tasks compared with other induced emotions that have a deleterious effect on reasoning (in most cases).

- MOST EMOTIONS LEAD TO GREATER RELIANCE ON HEURISTICS

- With the exception of sadness, most emotional states and moods will lead to greater reliance of heuristics in object judgments and decision-making. So, if balanced evaluation of a product happens to be the goal, we need to be careful about making marketing content too emotional.

There are many other learnings from emotion science that can intersect with the above summary, but we want to highlight just a handful that feel especially relevant to our work in customer insights. Interestingly, many of the effects here, such as the tendency for happy people to appraise almost everything around them more favorably, are moderated by another key variable – the salience of the content or topic. When content is salient, induced emotions are less likely to alter appraisals or orientation to the issue (see discussion by Fiske & Taylor, 2022, or check out our post entitled, “Content Salience Primes Message Effectiveness“). Additionally, recent evidence suggests that dispositional happiness and dispositional sadness (which function more like personality traits) will tend to override the effects of induced happiness and sadness on the quality of reasoning (Huntsinger et al, 2014; Huntsinger & Ray, 2016). The distinction between the emotion evoked by a piece of content and the general emotional tendency of an individual customer is always worth keeping in mind.

1 To keep Table 2 simple, we made the decision to exclude specific citations. Readers are encouraged to review the data for themselves via Aue & Okin-Singer (2015), Raila et al (2015), Fiske & Taylor (2022, pp.419-426 primarily), Blanchette & Caparos (2018), Blanchette & Richards (2010), Bisson & Sears (2007), Gollan et al (2010), Zuo et al (2023), Lench & Levine (2005); Wake et al (2020), Raghunathan & Pham (1999), Habib et al (2015), Ferrer et al (2020), Karnaze & Levine (2018), and Newell et al (2022, pp. 226-228, primarily).

Why Emotion-Cognition Dynamics Matter in Marketing

We suspect that our core point is probably obvious to readers, but just to be explicit, let’s put it plainly. Marketers and their agencies can benefit from having some fundamental understanding of the specific cognitive effects communications are likely to produce.

- CONSIDERATION #1: THINK IN ADVANCE: ARE MY INTENDED GOALS ALIGNED WITH THE EMOTION MY CONTENT IS LIKELY TO ELICIT?

- First, we want to be careful of which emotions we actually elicit with our content. Arming ourselves with some up-front knowledge about how emotions relate to downstream changes in thinking can help us to do this in a campaign-relevant way.

- For example, if your goal is to reinforce and strengthen existing behaviors, invoking anxiety or sadness is probably going to be counterproductive because these emotions may cause participants to reconsider past choices and consider how changes in their behavior might minimize future regret.

- On the other hand, if the campaign goal is to heighten empathy and deep consideration of patient experience, then invoking sadness might be precisely the emotional solution.

- CONSIDERATION #2: ARE WE DETECTING THE NUANCES OF CUSTOMER EMOTIONS ACCURATELY?

- Second, to be sure that we are tracking on the emotion-cognition states we have created, we want to be confident that we can measure customer emotions and cognitions with some nuance.

- Unintentionally eliciting anger or disgust, for example, can produce changes in attitudes and thinking that are obverse to what we’re trying to accomplish.

- As we discussed in “Accepting the Limitations of Self-Report in the Measurement of Emotion”, emotions are not only categorically diverse, but they can present with very subtle intensity, so paying attention to and measuring these differences is critical to evaluating what you are actually accomplishing with your content.

- CONSIDERATION #3: ARE WE MEASURING COGNITION OUTCOMES? THEY ARE JUST AS IMPORTANT AS EMOTION

- We also think that getting sharp measures related to elicited changes in cognition is essential.

- As we have argued, changing customers’ minds is not only a key early step in behavior change, but it is also a much more realistic near-term endpoint for evidence of the effectiveness of our communication efforts.

- So, our research techniques should be sensitive to the nuance of both emotion and the resulting shifts in cognition. While this is easier said than done, new tools and approaches can help us make this happen.

Our earnest belief is that life science marketing is in a position to take a more deliberate, thoughtful and evidence-based orientation to the role of emotion-cognition dynamics in our communication efforts and we hope that our several posts summarizing the available evidence can help to encourage this evolution.

To learn more, contact us at info@euplexus.com.

APPENDIX

Sidebar: Emotions as Dimensional Rather than Discrete

Some researchers advance the idea of a dimensional view of emotions. Rather than trying to think about the world of emotions as having a complex taxonomy with sharp boundaries between distinct types, these scientists advance the idea that all emotions are combinations of more basic components or “elements” that combine in different ways to produce the physiological/cognitive reactions that we call emotion. Dimensional models have changed over time and different researchers advance alternative versions of the concept. In models I am aware of, one dimension normally deals with the positivity or negativity of the experience (the valence). A second dimension might deal with the level of arousal experienced (calm vs. excited), whether the emotion involves tension (does the emotion make you feel tense or relaxed) or involve some kind of mental classification of the event. The idea is that anything we could call a discrete emotion can be more simply explained by placing it along each dimension, rather than trying to give the emotion some special distinct status. They argue this is a reason why emotions can be so subtly graded (think annoyance vs. anger vs. rage) and underpins the social necessity of having so many different words to describe our own subjective experiences of emotions (Barrett, Gendron & Huang, 2009).

Ultimately, we do not have a formal opinion on the neurological validity of the discrete vs. dimensional conceptualization of emotions. However, we do align with more recent investigations, which suggest that for practical purposes, humans act as if emotions are discrete (see, e.g., Cowen et al, 2019 or Hoffman et al, 2012). Reasonable people can continue to debate the question of dimensions vs. discrete emotions, however, when it comes to the role of emotions in persuasive communication research, and the kinds of effects that individual emotions produce, we side with psychologist and communication scientist Robin L. Nabi’s synthesis on the issue: While the dimensional approach to emotions has the advantage of conceptual simplicity and elegance, the discrete emotions perspective more than makes up for its complexity by offering gains in predictive accuracy relative to things like behavior change and changes in cognition (Nabi, 2010). At the end of the day, these are the kinds of practical learnings that we want when we apply scientific evidence to marketing.

About euPlexus

We are a team of life science insights veterans dedicated to amplifying life science marketing through evidence-based tools. One of our core values is to bring integrated, up-to-date perspectives on marketing-relevant science to our clients and the broader industry.

References

Angie, A. D., Connelly, S., Waples, E. P., & Kligyte, V. (2011). The influence of discrete emotions on judgement and decision-making: A meta-analytic review. Cognition & Emotion, 25(8), 1393-1422.

Aue, T., & Okon-Singer, H. (2015). Expectancy biases in fear and anxiety and their link to biases in attention. Clinical psychology review, 42, 83-95.

Barrett, L. F., Gendron, M., & Huang, Y. M. (2009). Do discrete emotions exist?. Philosophical Psychology, 22(4), 427-437.

Bisson, M. S., & Sears, C. R. (2007). The effect of depressed mood on the interpretation of ambiguity, with and without negative mood induction. Cognition and Emotion, 21(3), 614-645.

Blanchette, I., & Caparos, S. (2018). When emotions improve reasoning: The possible roles of relevance and utility. New Paradigm Psychology of Reasoning, 163-177.

Blanchette, I., & Richards, A. (2010). The influence of affect on higher level cognition: A review of research on interpretation, judgement, decision making and reasoning. Cognition & Emotion, 24(4), 561-595.

Chepenik, L. G., Cornew, L. A., & Farah, M. J. (2007). The influence of sad mood on cognition. Emotion, 7(4), 802.

Cowen, A. S., Elfenbein, H. A., Laukka, P., & Keltner, D. (2019). Mapping 24 emotions conveyed by brief human vocalization. American Psychologist, 74(6), 698.

Cosmides, L., & Tooby, J. (2000). Evolutionary psychology and the emotions. Handbook of emotions, 2(2), 91-115.

Ferrer, R. A., Taber, J. M., Sheeran, P., Bryan, A. D., Cameron, L. D., Peters, E., … & Klein, W. M. (2020). The role of incidental affective states in appetitive risk behavior: A meta-analysis. Health Psychology, 39(12), 1109.

Finucane, A. M. (2011). The effect of fear and anger on selective attention. Emotion, 11(4), 970–974.

Gollan, J. K., McCloskey, M., Hoxha, D., & Coccaro, E. F. (2010). How do depressed and healthy adults interpret nuanced facial expressions?. Journal of abnormal psychology, 119(4), 804.

Habib, M., Cassotti, M., Moutier, S., Houdé, O., & Borst, G. (2015). Fear and anger have opposite effects on risk seeking in the gain frame. Frontiers in psychology, 6, 124468.

Hoffmann, H., Scheck, A., Schuster, T., Walter, S., Limbrecht, K., Traue, H. C., & Kessler, H. (2012, October). Mapping discrete emotions into the dimensional space: An empirical approach. In 2012 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC) (pp. 3316-3320). IEEE.

Huntsinger, J. R., Isbell, L. M., & Clore, G. L. (2014). The affective control of thought: malleable, not fixed. Psychological review, 121(4), 600.

Huntsinger, J. R., & Ray, C. (2016). A flexible influence of affective feelings on creative and analytic performance. Emotion, 16(6), 826.

Karnaze, M. M., & Levine, L. J. (2018). Sadness, the architect of cognitive change. The function of emotions: When and why emotions help us, 45-58.

Lench, H., & Levine, L. (2005). Effects of fear on risk and control judgements and memory: Implications for health promotion messages. Cognition & Emotion, 19(7), 1049-1069.

Lench, H. C., Tibbett, T. P., & Bench, S. W. (2016). Exploring the toolkit of emotion: What do sadness and anger do for us?. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 10(1), 11-25.

Mellentin, A. I., Dervisevic, A., Stenager, E., Pilegaard, M., & Kirk, U. (2015). Seeing enemies? A systematic review of anger bias in the perception of facial expressions among anger-prone and aggressive populations. Aggression and violent behavior, 25, 373-383.

Nabi, R. L. (2010). The case for emphasizing discrete emotions in communication research. Communication Monographs, 77(2), 153-159.

Newell, B. R., Lagnado, D. A., & Shanks, D. R. (2022). Straight choices: The psychology of decision making. Psychology Press.

Nummenmaa, L., & Saarimäki, H. (2019). Emotions as discrete patterns of systemic activity. Neuroscience letters, 693, 3-8.

Raghunathan, R., & Pham, M. T. (1999). All negative moods are not equal: Motivational influences of anxiety and sadness on decision making. Organizational behavior and human decision processes, 79(1), 56-77.

Raila, H., Scholl, B. J., & Gruber, J. (2015). Seeing the world through rose-colored glasses: People who are happy and satisfied with life preferentially attend to positive stimuli. Emotion, 15(4), 449.

Sznycer, D., Cosmides, L., & Tooby, J. (2017). Adaptationism carves emotions at their functional joints. Psychological Inquiry, 28(1), 56-62.

Wake, S., Wormwood, J., & Satpute, A. B. (2020). The influence of fear on risk taking: a meta-analysis. Cognition and Emotion, 34(6), 1143-1159.

Zhu, X., Luchetti, M., Aschwanden, D., Sesker, A. A., Stephan, Y., Sutin, A. R., & Terracciano, A. (2023). The association between happiness and cognitive function in the UK Biobank. Current Psychology, 1-10.