Table of Contents

- Our Basic Contention on Self-Reported Emotions

- Important Terminology

- Some Things We Know from Emotion Science Research

- Limitations of Self-Reported Emotion

- Take-Home Points

Our Basic Contention on Self-Reported Emotions

In this post, we present a straightforward, evidence-based case for finding alternatives (or at least supplements) to self-report in the measurement of emotional experience as part of primary market research. While self-reports do have some very useful applications in our work, we believe they have limitations for real-time stimulus evaluation that is required for many types of studies (e.g., visual aid/concept testing, message evaluation). These limitations are specifically related to challenges with self-report as a vehicle for the measurement of emotional reactions. Emotions have a number of characteristics that make them imperfect targets for self-report.

- Emotions are highly transitory – some emotional experiences arise and recede within just a few moments

- Emotions are diverse, nuanced and distinctive – and can include extremely complex experiences such as mixed emotions (e.g., simultaneous feelings of fear and euphoria)

- The subjective experience of emotions is highly idiosyncratic from person to person

- Emotions impact multiple endpoints in real time

Taking these characteristics together, we believe that self-report exercises that rely on intellective tasks such as adjective pairing, or simple positive-negative feeling measures (such as those captured by emotion wheels or the AffectButton (Broekens & Brinkman, 2013) are at best blunt measures of customer emotionality. In cases where communications intend to produce highly specific outcomes in the hearts and minds of customers, course-grained self-report exercises will be of limited value.

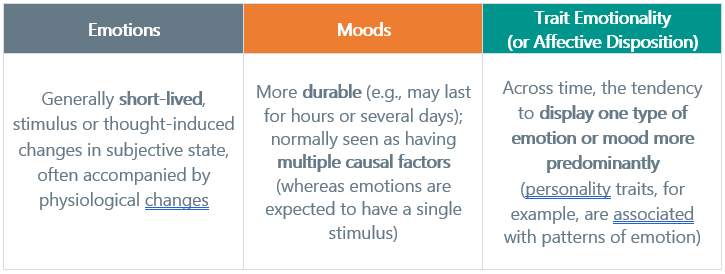

Important Terminology

As a starting point, it is important to distinguish between three different levels of emotional experience. These terms really mean something when it comes to the academic study of emotion and are particularly important to this discussion of self-report techniques. For example, the momentary/short-term vacillations in emotions are only weakly linked with longer-term patterns (see discussion by Houben et al, 2015).

In the context of this post, our focus is on the momentary, stimulus-induced emotion, as these are the target for marketers when we are looking at communications development. We definitely believe that moods and trait emotionality have a critical role to play but are more relevant to things like customer segmentations and explorations of the lived experiences of customers.

Some Things We Know from Emotion Science Research

To help get our arms around the limitations of using self-report exercises for emotion measurement, we think it will be helpful to understand some of the core learnings from recent integrations of the last 60 years of emotion science. In sharing these points, we are deliberately staying away from any theoretical point of view and focusing only on findings that have been repeatedly demonstrated and supported with meta-analysis. For readers who want to skip the details, here are the main points:

- Emotions are physiologically and experientially subtle and nuanced – they are finely tuned to the specific nature of the situations that bring them about.

- The kinds of stimuli that we test in market research contexts can be expected to produce modest but specific emotional reactions in customers.

- Different emotions have very different effects on downstream endpoints, including impact on cognition, evaluation, subjective experience and behavior/decision-making.

Each of these ideas contributes to the context from which we evaluate self-reported data on emotions.

- Nuanced “Populations” of Emotions: A fascinating learning comes to us from a 2018 meta-analysis led by Erika Siegel and a cast of other emotion researchers. This analysis focused on a range of physiological endpoints associated with the autonomic nervous system, including respiratory, cardiovascular and electroconductive responses. They wanted to explore if and how those endpoints varied systematically based on deliberate emotion manipulations (which we discuss more below). The analysis included 739 individual experiments with data obtained from ~29,000 humans, each focusing on the manipulation of anger, fear, sadness, happiness or disgust, and all using a neutral emotion within-subjects control condition. The central learning is that variations in multiple physiological endpoints does not conform to a specific “signature” for each emotion category. Rather the data suggests that emotion categories are subtle and varied – and very much tuned to the specific nature of the experimental setting. Their essential conclusion is that while thinking about types or categories of emotions is a reasonable starting point, we are better off thinking of these categories as “populations” of distinct sub-emotions. This would mean, for example, that an emotion like anger will manifest in a range of specific autonomic responses that are appropriate to the circumstances and reflective of the historical experiences and cultural learning of the individual. For our purposes, the key implication is that if we are interested in measuring real-time emotions with any degree of accuracy, we would need fairly refined ways of doing so.

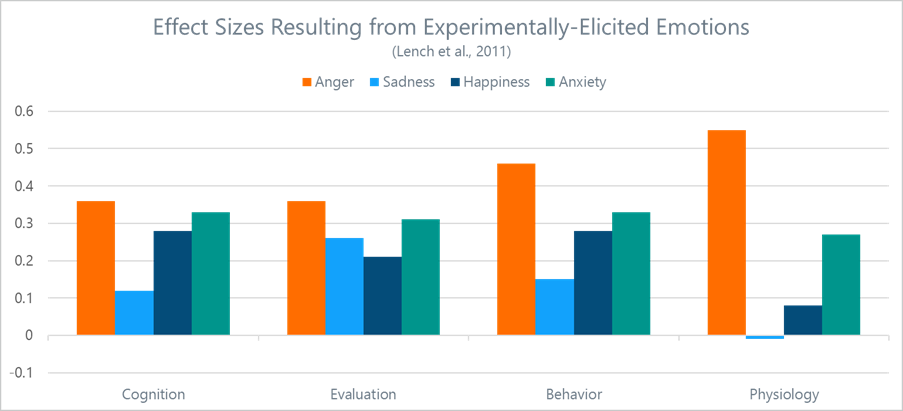

- Do Emotional Manipulations Work? To our knowledge, the most comprehensive examination of the techniques used to produce emotional reactions in experimental research was conducted by Lench, Flores & Bench in 2011. Their meta-analysis included 687 independent studies and nearly 50,000 human participants, and offers several insights for marketers and insights professionals that are worth absorbing. First,Lench et al showed that, across diverse endpoints (physiological, cognitive, etc.), human participants are, in fact, responsive to a variety of elicitation techniques relevant to our field. Diverse emotional responses can be produced using film, imagery, recollections of life events and even fictional or hypothetical events. Further, stimuli developed for the purpose of eliciting distinct emotional reaction (e.g., anger, sadness, contentment) have the capacity for specificity – that is, they get the emotional reaction they are looking for. For marketers this means that it is completely reasonable to expect evocative imagery and medical vignettes to produce authentic emotional reactions. And for insights professionals, this means we should be looking for ways to measure these effects with specificity. Figure 1 shows the simple aggregated effect sizes for these four endpoints across all studies that manipulated anger, sadness, happiness or anxiety versus a neutral control condition.

Figure 1. Multi-Endpoint Effects of Four Discrete Emotions from Experimental Tests

Naturally, these artificially induced emotions are associated with modest effect sizes – and academic researchers suggest that larger effects would be expected from emotions experienced “in the wild” (Kihlstrom et al, 1999). Nevertheless, this confirmation is useful and encouraging. It is also worth noting that a subsequent meta-analysis by Berrios et al (2015) confirmed that emotional manipulations such as those documented here also translate to scenarios involving mixed emotions. This underscores that it is possible for marketing-relevant content to invoke highly nuanced and complex emotional responses including competing emotions such as simultaneous happiness and sadness.

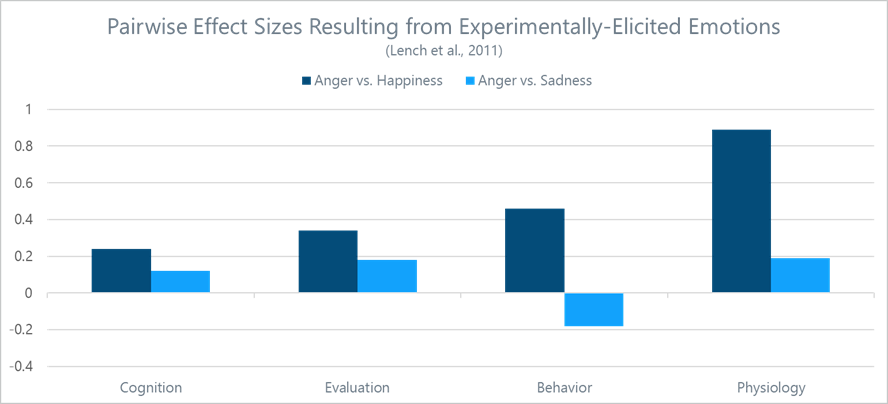

- Outcome Signatures for Discrete Emotions: While the Siegel et al analysis dealt with objective physiological reactions from emotion manipulation, some researchers are more concerned with the downstream consequences of emotion change. Another salient learning from the useful Lench et al meta-analysis is that specific emotions, as manipulated with the various techniques we just discussed, have substantially distinct effects across a range of downstream outcome measures. The outcomes coded for this study included changes in cognition, changes in judgments (e.g., associated with specific evaluation tasks related to various stimuli), changes in physiology (variously measured, but including things like heart rate, skin conductivity) and changes in behavior. To bring this to life (and simplify it), we isolated two pairwise sets of emotions in Figure 2 below. To understand these data, imagine two participants, each being exposed to an emotion-inducing experience. The first participant is made to feel angry, the second is made to feel happy. Then we evaluate each of the participants on specific cognitive, evaluative, physiological or behavioral responses to the subjective emotional experience. Finally, we want to compare our two participants across each of the four outcomes to see how big the differences between their reactions were.

Figure 2. Pairwise Effects of Four Discrete Emotions from Experimental Tests

To clarify how to read the data, consider the following summary points:

- Changes in cognition were more divergent for anger when compared to happiness than when anger is compared to sadness.

- Changes in physiology were naturally larger when comparing anger to happiness than when the comparison was to sadness.

- Note that for behavior the “negative” effect size simply means that the manipulations moved contrary to the researchers’ hypotheses – in this case the behavior response to sadness was larger than the response to anger.

Keep in mind that these data are a sub-sample of what the authors’ analysis reveals. But they are representative of the fundamental point, which is that different emotions tend to produce specific patterns of change in various downstream endpoints. As we will see in a subsequent post, these outcome signatures can be measured at an even more nuanced level when we unpack how discrete emotions influence facets of thought or cognition (Angie et al, 2011). For the moment, we hope that we’ve made the key point, which is that there’s reason for wanting to be precise when we think about the kinds of impact we expect to have with emotion-producing content.

Limitations of Self-Reported Emotion

The above suite of findings from emotion science sets the table for how we think about the use of self-report-based exercises for emotion evaluation. To-date, despite the proliferation of numerous styles of measurement, self-report remains the most common way of exploring emotions, and psychologists have developed numerous self-report tools and techniques to improve the quality and value of this type of information. But there are well documented challenges and limitations to the approach, and these limitations seem exacerbated in light of what we just learned about the subtlety and diversity of emotional experience.

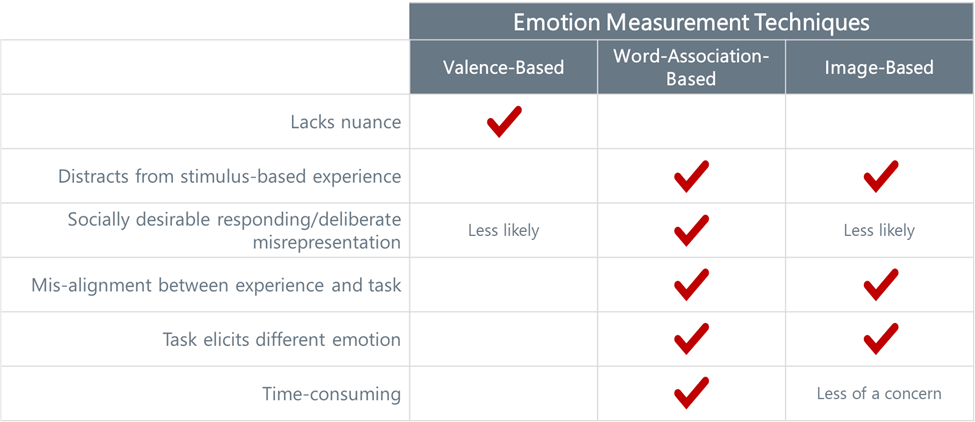

It is worth noting that most of the self-report systems for emotion measurement come in three basic forms. The first is a simple “affective valence” model, where the participant signals how good/bad they feel at a given moment. This can be accomplished with a Likert-type scale or with more elaborate techniques, such as the DialSmith© device commonly used in political advertising. Some variations, such as the Affect Grid system attempt to enrich this approach by adding a second axis (arousal) and having participants place themselves at an appropriate point in two-dimensional space to signify their subjective state. The second approach will usually involve word-association exercises, ordinarily using lists of descriptive adjectives that capture more nuanced characterizations of one’s current emotional state. The participant will read a list of words (sometimes a lengthy one) and then select the words that best match their current feelings. Examples include the PANAS scale (Watson et al, 1988) and the Discrete Emotion Questionnaire (DEQ). A third category of self-report instrument approaches involve the use of images or body representations where the participant chooses a picture or a body part to signify their feelings. Some interesting validation work has been done on these techniques (see discussions by Garcia-Magarino et al, 2017), and we do not have space for a full review here.

Among professional academic researchers, a handful of core limitations come up repeatedly around self-reported emotion (see interesting discussions in Porayska-Pomsta et al (2013) and the above-mentioned Garcia-Magarino et al (2017) article).

- Abstraction: They are too simplistic and lack the nuance and diversity of actual subjective and physiological experience (Mauss & Robinson, 2010). This may be especially true when we are talking about the modest facsimiles of emotion that stem from market research stimuli or lab-based elicitation of emotions.

- Distraction: Some are distracting and may cause participants to lose track of their own subjective experiences. In other words, by the time you figure out the self-report task, you have lost the subjective feeling you are trying to evaluate in the first place (Harley, 2015). This is more likely to be true of complex adjective lists associated with instruments like the PANAS or DEQ but would also apply to the body representation approach.

- Social Desirability: Socially desirable responding bedevils all self-report data to one degree or another (for a comprehensive review of the challenge, see Tourangeau & Yan (2007)). There are a variety of circumstances under which reporting of emotions might feel embarrassing or incriminating to participants. This may be linked to cultural or gender norms surrounding expression and discussion of emotions. (see Filkowsky et al, 2017; Mauss & Robinson, 2010).

- Word-Experience Gaps: There is also evidence that our descriptions of emotional experience can often depart from the momentary physiological and subjective experience that comes from the emotional manipulation (see Lindquist et al, 2013). The words we use to describe our emotional experiences are strongly shaped by cultural influence and past experience. We learn words that we are supposed to use when we experience a specific physiological reaction.

- Unintentional Emotions: Relatedly, some tasks may actually produce emotional reactions in their own right, which may enhance distraction or influence self-assessment in the moment. Think about it this way: How would your rating of an emotional experience change if the experience of evaluating that emotion turned out to be annoying or frustrating in its own right?

- Real Estate: They can be very time-consuming (Larson et al, 1999), which may lead to content tradeoffs that researchers would rather not make.

- Pollyanna Effect: Another aspect of self-report on emotional experience concerns the time lag between exposure to the stimulus and reporting of feelings. To get a flavor for why this matters, think about a concept test you have observed. Think about the initial responses that you get the moment after the concept is presented, and then think about the kinds of response you get when the participant is asked to “recap” her feelings and reflections on the concept at the end of the exercise. Very often, the recap will be more positive and less nuanced, with any criticisms more or less discarded. That is the effect of our natural tendency to recall positive aspects of our experiences. This Pollyanna Principle (see discussions by Kilstrom et al, 2015, and Pool et al, 2016) represents another potential threat to validity when using time-consuming self-report measures of emotional reaction.

Table 2. Some Acknowledged Limitations of Self-Report Exercises for Emotion Measurement

Clearly, market researchers and academics have good reasons for using self-report measures of emotion. They are face valid, easy to create and easy to administer. And there is some evidence of reasonable relationships to downstream behavior change1. Nevertheless, the above limitations underscore a core point made by Pekrun and Schutz (2011) in their major review of emotion measurement literature: conventional self-report-based exercises are not terribly good for the measurement of moment-to-moment changes in emotional state. They call for alternative and multi-method approaches that, at a minimum, would supplement self-report for this purpose (a position that is supported by Mauss & Robinson, 2010 in their literature synthesis). We agree and will discuss some alternatives in a separate post.

Clarifying Sidebar: When is Self-Report GOOD for the Exploration of Emotions?

We want to be clear that we are NOT contending that self-report has no role in evaluating customer emotionality. Most instruments for the assessment of emotional experience are intended to capture mood or emotional disposition rather than moment-to-moment experiences of emotion. Happily, this seems to work relatively well. For example, there is good correspondence between self-reported moods and overall emotionality and clinician-evaluations of those same endpoints. For example, this has been demonstrated in a major meta-analysis of studies of depression (Cuijpers et al, 2010). We will discuss this in detail in a separate post.

1 In the interest of space-saving, we did not include these data, but interested readers may want to consult Table 2 of the Lench et al (2011) meta-analysis, which offers at least a loose quantification of this relationship. In many market contexts, self-reported experience of emotion is a decent predictor of behavior. However, as we explain in our subsequent post on upstream drivers of behavior change, healthcare creates serious structural barriers that disrupt that predictive power.

Take-Home Points

- POINT #1: Marketing Stimuli Can Reliably Invoke Distinct, Real-World Emotions

- There is strong evidence that the kinds of stimuli we use for market research when testing things like ad content do, in fact, produce emotional responses.

- Naturally, these are likely to be much more muted than the subjective experience of emotions in natural social environments.

- POINT #2:Emotions are Diverse and Produce Distinct Outcomes

- Emotion science makes clear that emotions are diverse, subtle, and specific, and produce specific types of outcome effects that are distinct from one emotion to another.

- POINT #3: Various Self-Report Exercises Exist to Measure Emotional Experience

- A range of different types of self-report exercises have been designed and used in both academic and market research to tap into the subtlety of real-time emotional experience, including complex word association exercises.

- POINT #4: But, These Self-Report Exercises are Severely Limited

- Unfortunately, these approaches come with a litany of challenges that make them, at best, insufficient for accurate characterization of moment-to-moment emotional experience.

- These limitations, coupled with muted emotional experiences suggest a need for highly sensitive measurement.

- POINT #5: Alternatives to Self-Reported Emotions are Likely Warranted in Many Cases

- Researchers wanting to capture emotional reactions to marketing stimuli should explore multi-method, multi-endpoint alternatives to supplement self-report.

If You Enjoyed These Points, You Might Also Like: Most people have an intuition that customer decision-making is strongly shaped by emotions, because we can feel these effects in our own lives. At the same time, we also have the nagging feeling that decision-making in healthcare may be different. Surely emotion plays a role in the selection of medicines, but what about data, reasoning and habit. We help you make sense of this in our upcoming post entitled, “Evoking Emotion to Set the Stage for Behavior Change”.

To learn more, contact us at info@euplexus.com.

About euPlexus

We are a team of life science insights veterans dedicated to amplifying life science marketing through evidence-based tools. One of our core values is to bring integrated, up-to-date perspectives on marketing-relevant science to our clients and the broader industry.

References

Angie, A. D., Connelly, S., Waples, E. P., & Kligyte, V. (2011). The influence of discrete emotions on judgement and decision-making: A meta-analytic review. Cognition & Emotion, 25(8), 1393-1422.

Berrios, R., Totterdell, P., & Kellett, S. (2015). Eliciting mixed emotions: a meta-analysis comparing models, types, and measures. Frontiers in psychology, 6, 133792.

Cuijpers, P., Li, J., Hofmann, S. G., & Andersson, G. (2010). Self-reported versus clinician-rated symptoms of depression as outcome measures in psychotherapy research on depression: a meta-analysis. Clinical psychology review, 30(6), 768-778.

Harley, J. M. (2016). Measuring emotions: A survey of cutting edge methodologies used in computer-based learning environment research. Emotions, technology, design, and learning, 89-114.

Harmon-Jones, C., Bastian, B., & Harmon-Jones, E. (2016). The discrete emotions questionnaire: A new tool for measuring state self-reported emotions. PloS one, 11(8), e0159915.

Houben, M., Van Den Noortgate, W., & Kuppens, P. (2015). The relation between short-term emotion dynamics and psychological well-being: A meta-analysis. Psychological bulletin, 141(4), 901.

Kihlstrom, J. F., Eich, E., Sandbrand, D., & Tobias, B. A. (1999). Emotion and memory: Implications for self-report. In The science of self-report (pp. 93-112). Psychology Press.

Larsen, R. J., & Fredrickson, B. L. (1999). Measurement issues in emotion research. Well-being: The foundations of hedonic psychology, 40, 60.

Lench, H. C., Flores, S. A., & Bench, S. W. (2011). Discrete emotions predict changes in cognition, judgment, experience, behavior, and physiology: a meta-analysis of experimental emotion elicitations. Psychological bulletin, 137(5), 834.

Lindquist, K. A., Siegel, E. H., Quigley, K. S., & Barrett, L. F. (2013). The hundred-year emotion war: are emotions natural kinds or psychological constructions? Comment on Lench, Flores, and Bench (2011).

Mauss, I. B., & Robinson, M. D. (2010). Measures of emotion: A reviews. Cognition and emotion, 109-137.

Pekrun, R. & Schutz, P. A. (2011). Implications and Future Directions for Inquiry on Emotions. Emotion in Education, 313.

Pool, E., Brosch, T., Delplanque, S., & Sander, D. (2016). Attentional bias for positive emotional stimuli: A meta-analytic investigation. Psychological bulletin, 142(1), 79.

Porayska-Pomsta, K., Mavrikis, M., D’Mello, S., Conati, C., & Baker, R. S. (2013). Knowledge elicitation methods for affect modelling in education. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 22(3), 107-140.

Siegel, E. H., Sands, M. K., Van den Noortgate, W., Condon, P., Chang, Y., Dy, J., … & Barrett, L. F. (2018). Emotion fingerprints or emotion populations? A meta-analytic investigation of autonomic features of emotion categories. Psychological bulletin, 144(4), 343.

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. Journal of personality and social psychology, 54(6), 1063.

Tourangeau, R., & Yan, T. (2007). Sensitive questions in surveys. Psychological bulletin, 133(5), 859.