Table of Contents

- Overview: A Refreshed View on Product Attributes & What They Mean

- Product Attributes as Success Levers

- Product Attributes as Quality Cues for Customer Decision-Making

- What Attributes Are Your Customers Paying Attention To?

- Product Attributes & Cognitive Heuristics

- Take-Home Points

Overview: A Refreshed View on Product Attributes & What They Mean

As a company, we have been impressed by the proliferation of what we call marketing-relevant science since the turn of the millennium. The amount of data – experimental and correlational – that is now available to inform us about marketing-relevant topics is immense. And whatever your views on behavioral and social science might be, it seems obvious that there are things we can and should learn from all this data. What personally excites me is the degree of precision and nuance that has emerged around so many complex, common issues that pertain to our practice as professionals. One such issue is a subject that many of us take for granted: The way that we think about product attributes and how customers relate to them. When I first came to the life science industry, we were just coming out of the Brand Wars era of the 1990s. At that time, the orthodox viewpoint that product value (as felt by the customer) was something like the sum of the value assigned to its product attributes or benefits. With this “bundle of attributes” orientation, almost any attribute could be seen as the key to successful brand differentiation and commercial success. Thanks in part to the increasing role of psychology in marketing and the practice of customer insights, it seems that we have the insights necessary to evolve to a more accurate view of product attributes and how customers relate to them.

This short article will synthesize scientific work that deals with the importance of product attributes and how they are used in actual product evaluations and decision-to-use scenarios. Specifically, we will look at:

- How important product attributes are in the overall mix of considerations that contribute to product success

- How product attributes actually contribute to the processes of product quality evaluation and product selection decisions

We will see that some industry standard assumptions about how customers use product attributes are not supported by evidence. And we will propose a more real-world way of thinking about product attributes that we believe will help marketers to convey the value of brands more efficiently and effectively.

Product Attributes as Success Levers

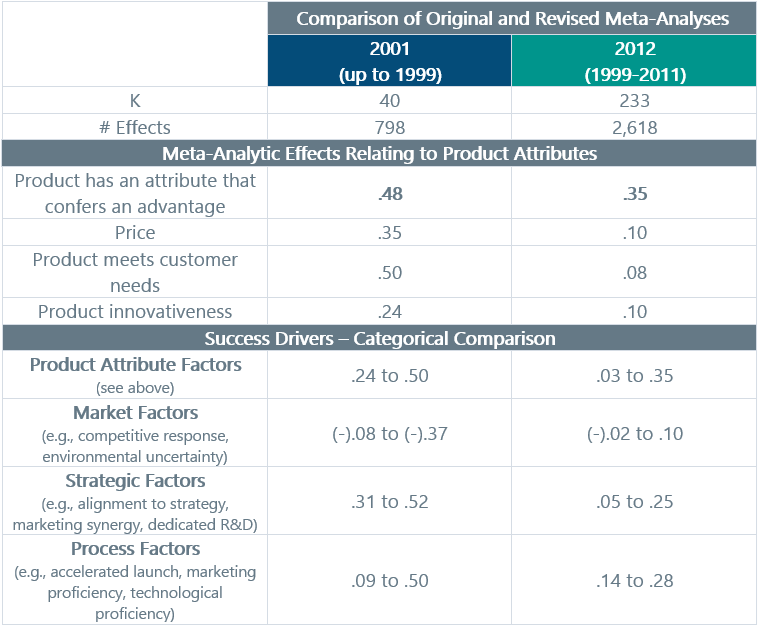

We will start with a pair of seminal meta-analyses, the first published in 2001 and the second in 2012, which looked at just about the most fundamental question you could ask in business: What factors account for new product success?1,2 Clearly, any one of us could develop hypotheses about the answer to that question, and many individual case studies adduce different causes for product success. These meta-analyses are ambitious because they boil down these complex business cases into quantifiable factors that can be compared across the cases. We only have space to highlight a few findings topical to this article, but we strongly recommend that readers seek out the original papers because they have a lot of great things to say. The researchers in the 2001 study looked at a wide range of success factors, including aspects of firm strategy, competitive context (e.g., counter-messaging and competitive response), and launch-process characteristics. They also looked broadly at the relationship between the product and the customer. Product success was measured on outcomes like total sales, market share, profit attributable to the product and ROI. The first study synthesized research published up to 1999, and the second analysis, conducted by another group of researchers, included only studies that had been conducted since the publication of the first. This allows us to examine the stability of the findings. The second study also includes studies from 17 different countries, whereas the 2001 study includes studies from the United States and a narrow range of Asia-Pacific markets (though the exact number is not reported and hard to confirm). Note the raw difference in the number of coded studies that were conducted in the 12 years between the two publications – another illustration of the profusion of marketing-relevant science.

Because this article is about the role of product attributes and their importance, I’m focusing on the insights that are centered on those factors. Some comparative results are summarized in Table 1 below, but here are the core take-aways

- In both meta-analyses, we can see that the effect sizes related to product attributes are generally larger (i.e., more important to product success) than the effects from most other driver categories. For example, product features are at least as important as brand strategy factors, and execution-related factors, and in most cases, more important.

- Second, when thinking about product attributes, the most important thing is for a product to have a key differentiating feature vis-à-vis its competition. Price is less important than having a differentiating feature. So is the innovativeness of the product.

To put a fine point on it, finding that one big differentiating feature is literally among the top drivers of product success – and in some cases, it will be the most important. Almost everything else we do strategically, structurally and promotionally to support the product is going to be less critical than finding that one key attribute you can highlight to make your product stand out.

Table 1. Product-Related Attributes as Derivers of New Product Success

Another thing to notice immediately is that the effect sizes and ranges in the 2012 reboot are much smaller than those of the 2001 study. The authors attribute this to a time-based attenuation of the relationship between predictors and product success (meaning they believe that market forces have changed over time such that new drivers of product success have emerged). My suspicion is that they are half-right, but I suspect the larger reason for the differences deals with the breadth and diversity of markets that were studied. The 2012 study includes studies conducted for products originating in 17 different markets, whereas the 2001 study includes a narrower set of markets. The authors themselves emphasize the importance of cultural differences that were coded in the 2012 study, which were statistically important mediators. Overall, even accounting for market evolution and the diverse characteristics of country-level and regional effects, finding and promoting a key differentiating attribute remains at the top of the driver pile.

Product Attributes as Quality Cues for Customer Decisions

So, clearly, it makes sense for us to care about specific features of products from a business perspective. For me, the next question is always, how do physicians and patients evaluate product attributes and use that information to make decisions? Whether you come from the perspective of classical economics, judgment and decision-making research or even the field of animal behavior, you have most likely been conditioned to think that our evaluations of objects (such as new products) are driven by the valuation and summation of all possible/available product features. The premise is appealing – it feels coherent to think of a product as representing a bundle of features. It also implies that every attribute must have something to contribute to how customers value products.

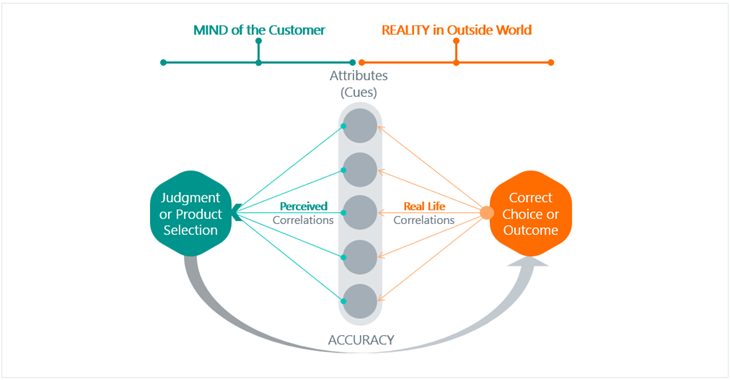

In the world of judgment and decision-making, which is a big part of my own educational background, the overarching model that one would tend to use when thinking about product attributes is called the Lens Model (conceived by a very brilliant psychologist with a perfect name: Egon Brunswik), which is depicted in simplified format in Figure 1 below. We framed this illustration of the model such that it focuses on the idea of a product decision, but the actual model generalizes very widely to most types of decisions. This framework is simpler than it looks, and the basic ideas are as follows.

- Out in the real world, every decision comes to us with informational cues. If you are buying a car, you look at the brand, the mpg rating, and other features to give an index of which car represents the best decision for you. If you are evaluating a candidate for a job, you are looking at things like writing samples, their fluency in speaking and their resumes. And in the case of evaluating the merits of a medication, the product attributes presented in a promotional rep visit would be included in this set of cues.

- The cues are correlated to greater and lesser degrees with good or “correct” decisions. Some cues are better than others for any given decision scenario. The cues are the only thing we can go on when making our judgement of a product, and ultimately serve as the basis for our decisions. And the cues are often imperfect or incomplete.

- In our own minds, we evaluate the quality of the product based on our interpretation of the cues. So, in the case of product evaluation, how accurately and completely we process the information about product attributes determines how we judge the product.

- Preference between two (or more) options in any decision scenario is driven by our arithmetic evaluation of the available quality cues from each option.

- The end.

If this sounds familiar to you, it is likely because this type of “rationalist” thinking is endemic to economics, computer science, animal behavior and, more locally, in the underlying psychological assumptions associated with the “conjoint family” of methods so familiar in the world of marketing. When we apply this idea to product selection, we imagine that, when a customer is comparing two products, she is literally tallying up all the information about each product attribute and comparing the running tally between her choice options. In concept, this process is simple and elegant.

But is this what really goes on in the minds of customers?

Figure 1. A Slightly Simplified Picture of the Lens Model for Decision-Making

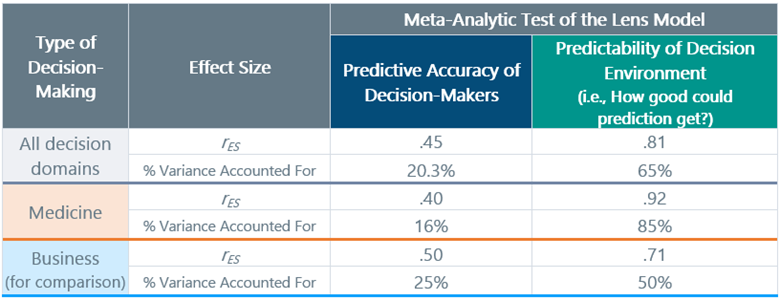

Experimental work designed to test how cues relate to decision-making is actually quite difficult and expensive to do, but over time enough of these studies have emerged to allow for systematic meta-analysis. A 2013 paper offers the most rigorous synthesis I have been able to find on the use of the Lens Model in decision-making, integrating k=49 experiments and n=1,159 total human participants.3 I appreciate this work because it not only gives us a sense of how effectively people pick up on and synthesize all the cues (attributes) they are given when they are making decisions, but also shows how this differs across areas of decision-making (e.g., medicine versus business). The studies included involve experiments where people receive a set of cues and then must make a judgment, or a decision based on that information. The meta-analysis of these studies reveals that humans of all stripes working in various types of decision-making environments do not make decisions in a way that aligns with the premise of complete information integration based on available cues. To put this differently, in these experiments, they ARE using information cues that are provided in the decision context, but they are not using them to their full potential. You can see this by looking at the meta-analytic correlation (rES=0.45) between executed decisions and the actual “best possible” decision based on the cue information provided in the experiments. Interestingly, the analysis also looks at the ceiling for how completely and effectively cue information could have been interpreted in the best-case-scenario (see right hand column). By comparing the blue and green columns, you can see the gap between real human cue integration and decisions with the “best possible” predictions in each environment. The gaps are pretty wide. Neither I nor the authors of that analysis are suggesting that the decisions being made are “bad.” Rather, they suggest the humans evaluating choice options with multiple informational cues are operating in a “sub-optimal way.” They are either ignoring some information or incorrectly interpreting it in their judgments. It is also interesting to note that even participants flagged specifically for having a high level of expertise in the decision domain do not integrate all the information properly.

Table 2. How Well Does the Lens Model Align to Reality?

So far, in my opinion, we’re learning some very interesting things. Product features are absolutely critical to convey because they are the prime movers of product success. But simultaneously, we are seeing evidence that people do not use attribute-like information cues to the extent that they could in real decision-making. This feels like the kind of learning that we would expect to get from a behavioral economist, where we have been endlessly showered with experimental reminders that humans are not “information-optimizing-utility-maximizers”. So, for those of you familiar with that literature, these findings may not be surprising.

What Attributes Are Your Customers Are Paying Attention To?

If you are a marketer or insights professional, you might now be wondering if this kind of failure to integrate cues is playing out when customers evaluate our product profiles in PMR settings. Despite all the admonitions from psychological science about human cognitive imperfection, when it comes to thinking about product features, we still tend to revert to that classic economics-style of thinking. For example:

- We tend to assume that more product features will make our product (or profiles of products) more appealing to customers.4,5

- We assume that customers read and integrate all the information in a product profile when we do conjoint or DCM-based exercises in PMR.

- We expect (hope?) physicians to compare and contrast all the features of existing products when they are choosing products for patients.

Naturally, these assumptions are subject to empirical testing, and the Lens Model meta-analysis would seem to suggest that we should not be too cavalier about them.

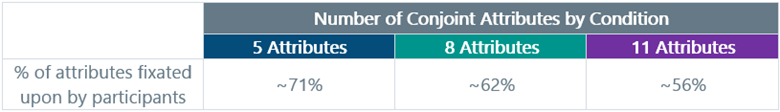

Whenever possible, we strongly prefer to answer this kind of question with meta-analytic evidence; however, there is a huge gap in the scientific literature concerning the study of exactly how decision-making actually takes place during product testing experiments. As such, we need to rely on the tiny amount of experimental data that exists. The best study I have found on this fundamental question is a 2021 study from the journal Political Analysis.6 The researchers used eye-tracking to evaluate what participants are doing when they completed a DCM-style experimental exercise comparing the qualities of political candidates. Eye tracking is one solid technique for evaluating customer attention, and though others exist, I think it is highly appropriate for answering the question how customers are collecting and processing information about product attributes as we typically present them in market research. There were several conditions in their experiment, the most relevant of which involved increasing the number of candidate attributes displayed. The experimental conditions showed product profiles with 5-, 8- and 11-attribute profiles. The dependent variable was preference for one candidate over the other. They recruited 122 participants from the Duke University student body as well as people from the surrounding community. And the attribute/level impact was assessed via both the fixation time associated with each attribute and the ordinary regression-based assessment derived from the selection of candidates.

For our purposes, the most important finding was that, as the number of product attributes (and thus the length and complexity of the TPP) increased, the proportion of the attribute content that captured visual attention diminished systematically. So, even in experiments where the participants are incentivized to read all the available attribute information (cues about product value/quality), they don’t. In fact, they ignore a good chunk of the attributes.

Table 3. Attention to Attributes Narrows as Product Profiles Become More Complicated

There was another critical finding from this study: Even as the number of “digested” attributes declined, the marginal value of all the tested attributes remained basically unchanged! The non-trivial implication is: Only a few attributes were really driving product preference and choice in the first place. The eye tracking data also suggests that the participants do exactly what cognitive psychologists would expect: They go to the information that is most important to them and use that to make an efficient determination about the choice option. A final finding that may surprise some readers is that only 4 of the 11 attributes were major drivers of decision probability – and that was true for both conventional derived assessment and based on eye tracking fixation.

If we look back at the evidence from earlier in this post, we can start to put the pieces together:

- Even in environments where good outcomes/decisions can be made based on aggregating the information about attributes/features of the situation, even experts don’t do nearly as well as they could. This suggests that people generally do not use all the available information.

- Similarly, in product evaluations in market research settings, we can see that participants are not even reading all the information they could use to make a product evaluation or to choose between two product options.

- When we increase the number of attributes/features that need to be considered, people actually pay attention to less of the information. When stimuli are complicated, the tendency is to look at fewer attributes, not more. Please read that again, because if it is happening in market research where humans are being paid to process information, you can be reasonably sure that their real-world behavior patterns will not be much better.

Hopefully, the data we have shown thus far has persuaded you that, at a minimum, there will be many cases where our customers are not going to care about, focus on or use all the product-based information we might want them to. But if they are not making decisions based on all the available information or all presented attributes, what are they doing?

The answer is in adaptive cognitive heuristics.

Product Attributes as Cognitive Heuristics

Much of human decision making relies on what cognitive psychologists call heuristics. Heuristics are cognitive adaptations designed to help make decision-making reasonably time-efficient and easy without sacrificing too much in terms of outcome quality. While conventional decision-making theory assumes that 100% of available information is captured, processed and weighted into the decision, cognitive heuristics models assume (almost) the opposite: Only the most relevant information is considered and decisions can be based on as few as one single information cue. Researchers have documented evidence for a fairly large number of different cognitive heuristics that humans use in different choice situations,7 and it is also clear that there is a lot of individual difference in terms of which heuristics are deployed by any particular person.8 But they all work on similar principles, focusing on using partial information as efficiently and accurately as possible. The science is also clear that, in most domains of decision-making, heuristics are the operating mode of human decision-making.

Here’s an example of how a cognitive heuristic works. Assume you are making a decision between two options, each of which includes some information cues. A heuristic assessment of the object could go as follows.

- Start with the piece of information that is most important to you (Cue 1) and look at how both options perform on that cue.

- If Cue 1 gives you enough information to choose between the options, make decision. If not proceed to Cue 2.

- Evaluate Cue 2 for both options.

- If Cue 2 gives you enough information, make decision. If not proceed to Cue 3.

- Repeat until the decision between the two options is made.

Does this feel at all familiar to you? My guess is that most readers can recall making an Amazon purchase or a Netflix selection based on a similar process.

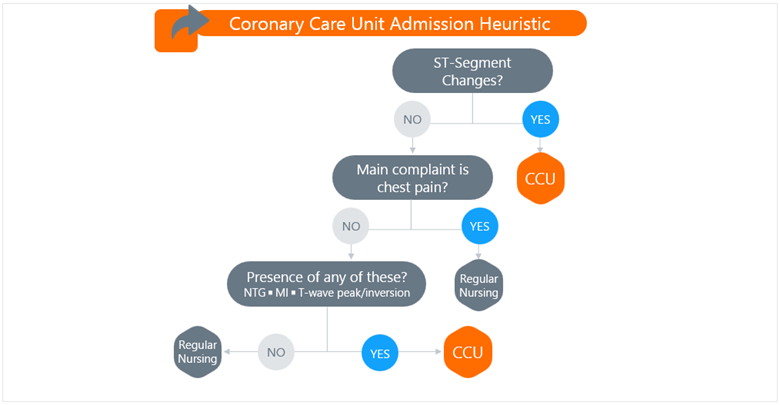

Many people believe that this kind of decision-making can lead to high error rates, but researchers have demonstrated that very often they produce outcomes that are as good as much more complex styles of decision-making, including statistical models. Figure 2 below shows an example of a medical decision-making heuristic that was developed to improve the speed and accuracy of admission decisions for patients who were presenting in the ER with complaints of chest pain. Evaluation of potential coronary events can be time consuming and costly, and they have the unfortunate potential for high error rates. Take a look at the decision nodes and you’ll see that each step in the tree is a yes/no evaluation. When compared to physicians working through their ordinary diagnostic processes, the heuristic tree in Figure 2 not only reduced the proportion of patients who were incorrectly admitted to the critical care unit by roughly half (i.e., reduced “false positives”), it also increased the rate of patients admitted to the CCU who actually needed to be there (i.e., reduced “false negatives). Other examples of the effective use of heuristics in medical decision-making include pain management decision in ER settings, the management of atrial fibrillation and drug selection for depression.

Figure 2. A Real-Life Example of Heuristic-Based Decision-Making in a Complex Medical Scenario

This example heuristic cascade was developed by cardiologists at the University of Michigan to help physicians make efficient yet almost-always-correct decisions about whether a patient presenting with MI symptoms should be admitted to the coronary care unit or monitored in a regular hospital nursing bed.9

This simple man-made heuristic tree has all the classic characteristics of the types of adapted cognitive heuristics that cognitive psychologists believe we are born with:

- It is simple and fast, with a maximum of three piece of information collected

- It is non-compensatory, meaning that users are not weighing one piece of information against another. Instead, the information is processed and used on a one-at-a-time basis.

And the fact that this simple heuristic can achieve better diagnostic decisions amplifies the time and efficiency value. I should note that similar kinds of heuristics have been tested against pretty stiff competition, including different types of regression models. In virtually all cases, the simple heuristics can almost match the predictive accuracy of complex statistical models, such as neural networks.10 It’s quite impressive. So, cognitive psychologists argue, it makes sense that these kinds of tools would evolve over time – they meet a lot of needs by balancing speed, ease and accuracy.11

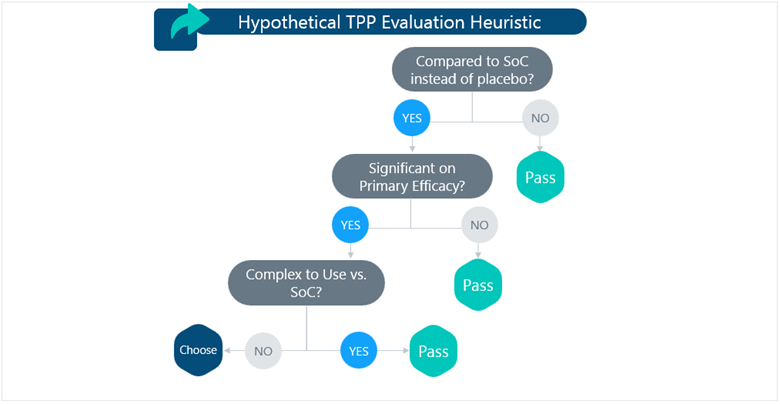

With this idea in mind, we can turn back to the question of how product attributes might actually be used in product evaluation scenarios. We can envision several different settings in which a product evaluation occurs. For example, we ask customers to compare and choose between products in market research settings. Here, they are often required to not only compare between products, but also to compare variations within products. This would be the case in a typical study deploying conjoint or DCM-type exercises meant to explore the tradeoffs between product features. To me, this kind of exercise simulates something akin to an initial evaluation of a newly-approved product – that is, the decision to try the product. Another scenario when product attributes are evaluated takes place when a physician is choosing a drug for a particular patient. Presumably, this kind of decision reflects a world where the physician has already made a decision about the overall merits of the product and is now deploying it for real clinical work. We can envision heuristics that could operate in both situations.

Figure 3. Illustrative Model of Hypothetical TPP-Evaluation Heuristic

The hypothetical heuristic in Figure 3 could apply to a situation where a physician is evaluating multiple simultaneous TPPs in a DCM-style exercise. Here, the participant evaluates a maximum of 3 product attributes to make their decision. Why this particular heuristic? Well, in a research study, we often show many profiles to customers, and the customer figure out quickly that the tasks are repetitive. If you know that you have a responsibility to provide a quality assessment for a large set of products, what’s your strategy? In my mind, the appropriate answer is something like what you would do if you were culling large numbers of resumes: Pick a few criteria that would separate solid candidates from weak ones, and then ignore everything else.

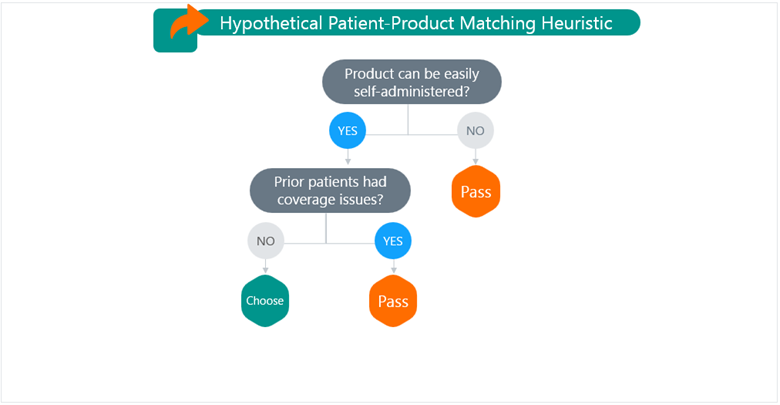

Now let’s imagine the scenario where a physician is trying to determine which medicine is the right one for a specific patient. For the sake of discussion, let’s suppose this patient is dealing with an emergent age-related autoimmune disorder. He is presenting with moderate symptoms that are somewhat disruptive to his ADLs, but not debilitating. He must travel almost an hour to get to the treater’s office. Let’s imagine the physician has three indicated products to choose from. How complex is the patient-product matching process? More specifically, which product attributes are getting the attention in this situation? The truth is that we don’t know. But we can be very confident that the physician is not going through some complex evaluation where they compare all the attributes of all three product options. Instead, the science of heuristics would suggest something much more simple. Based on the patient cues we have been given, I propose something like the model in Figure 4 below.

Figure 4. Illustrative Model of a Patient-Product Matching Heuristic

Here, the main product attribute that is getting the physician’s focus is the route-of-administration. Can this patient self-administer the products? If not, they are non-starters. In some conditions, that single cue might narrow your options to one product. This physician is also practical, so they ask themself if any of the medicines have led to problems for patients in terms of coverage or unexpected OOP costs. Based on this second memory-based cue, the physician makes a choice. Naturally, we can also concoct plenty of situations where the patient-product match would necessitate consideration of a larger number of product features. Keep in mind that I’m assuming the physician is already highly familiar with the products he/she is choosing between.

Whether you think my hypothetical heuristics in this article are any good is up to you. But hopefully, the experimental evidence we discussed earlier has shown that, at a minimum, this kind of minimalist approach to information use in product evaluation is the norm, not the exception.

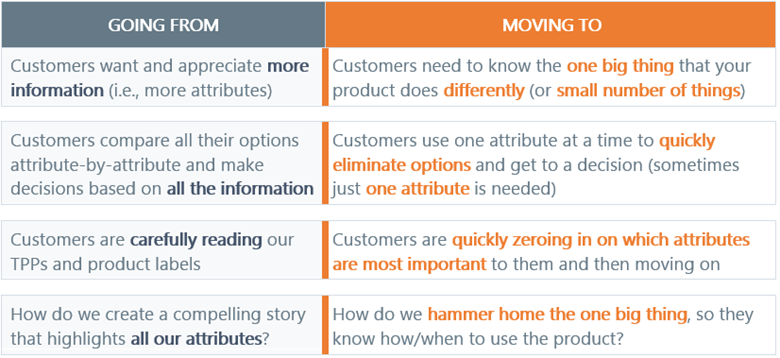

For me, all this evidence genuinely necessitates a re-thinking on how we approach the use of product attributes in marketing and in the practice of primary research. We’ve tried to sum up a set of simple suggestions that reflect both the realities of marketing practice and the science.

Table 4. Suggestions for Refining How We Approach Product Attributes

While we absolutely understand that some brands and brand stories are inherently complex, we still maintain that we should not fool ourselves into thinking that treaters and patients are going to digest all the subtle features of our products. This may be especially true in light of the increasing product density that has emerged in many disease settings. When it comes to promoting on product attributes, the KISS (Keep It Simple, Stupid) principle would appear to be an appropriate mantra.

Take-Home Points

- POINT #1: FIND THE DIFFERENTIATING THING

- Finding a differentiating product attribute is an absolute cornerstone of product success. That process is at least as important as anything else we can do in marketing.

- POINT #2: PEOPLE WILL NOT ABSORB ALL INFORMATION AVAILABLE

- But the idea that humans will read, digest and use information on numerous product attributes when they are making decisions is not supported by evidence.

- POINT #3: HEURISTICS ARE UNAVOIDABLE IN RESEARCH & REAL LIFE

- Humans, including physicians, generally take a heuristic approach to both product judgment and product decision making – meaning they use just a small handful of cues rather than all available information. In real life, when people are busy and overwhelmed with information, we should assume most customers will narrow their focus to just a tiny number of attribute cues.

- It is not realistic to imagine that customers will care about every subtle feature of your product. Moreover, the experiments we summarized here suggest that they probably won’t even read all of the attributes we present in a TPP. If they won’t pay attention to every attribute in a PMR setting, you can be sure they won’t do it in real life.

- POINT #4: TESTING MORE ATTRIBUTES IS NOT NECESSARILY BETTER

- Testing large numbers of attributes will likely give you a false sense of how customers will make decisions in real-life.

- POINT #5: REMEMBER, CUSTOMERS JUST NEED ONE GOOD REASON

- Whenever we can, we should focus on promoting our products using as few attribute cues as we can. Sometimes, there can be real value in focusing on just one good reason to use your product.

To learn more, contact us at info@euplexus.com.

About euPlexus

We are a team of life science insights veterans dedicated to amplifying life science marketing through evidence-based tools. One of our core values is to bring integrated, up-to-date perspectives on marketing-relevant science to our clients and the broader industry.

References

1 Henard, D. H., & Szymanski, D. M. (2001). Why some new products are more successful than others. Journal of marketing Research, 38(3), 362-375.

2 Evanschitzky, H., Eisend, M., Calantone, R. J., & Jiang, Y. (2012). Success factors of product innovation: An updated meta‐analysis. Journal of product innovation management, 29, 21-37.

3 Kaufmann, E., Reips, U. D., & Wittmann, W. W. (2013). A critical meta-analysis of lens model studies in human judgment and decision-making. PloS one, 8(12), e83528.

4 Thompson, D. V., Hamilton, R. W., & Rust, R. T. (2005). Feature fatigue: When product capabilities become too much of a good thing. Journal of marketing research, 42(4), 431-442.

5 Schwartz, B. (2015). The paradox of choice. Positive psychology in practice: Promoting human flourishing in work, health, education, and everyday life, 121-138.

6 Jenke, L., Bansak, K., Hainmueller, J., & Hangartner, D. (2021). Using eye-tracking to understand decision-making in conjoint experiments. Political Analysis, 29(1), 75-101.

7 Neth, H., & Gigerenzer, G. (2015). Heuristics: Tools for an uncertain world. In Emerging trends in the social and behavioral sciences (pp. 1-18). Wiley Online Library.

8 Newell, B. R., Lagnado, D. A., & Shanks, D. R. (2022). Straight choices: The psychology of decision making. Psychology Press.

9 Marewski, J. N., & Gigerenzer, G. (2012). Heuristic decision making in medicine. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience, 14(1), 77-89.

10 Buckmann, M., & Şimşek, Ö. (2017, August). Decision heuristics for comparison: How good are they?. In Imperfect Decision Makers: Admitting Real-World Rationality (pp. 1-11). PMLR.

11 Gigerenzer, G. (2021). Embodied heuristics. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 711289.