Table of Contents

- Introduction

- The Surprising Truth: Data Usually Wins Over Narratives

- But As Usual, Healthcare is Different

- What Does a Good Story Buy You?

- Take-Home Points

Introduction

Are humans more likely to be persuaded by statistical information and data, or are they motivated by personal narratives, anecdotes and stories? In the world of communication research, this question is not trivial. It has even received some attention in the media, largely due to the popularity of the behavioral economics movement. Based on that attention, I suspect many readers would guess off the bat that narrative-based communications are more persuasive most of the time. As the now-famous psychology duo, Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman noted, people tend to find statistical information to be non-intuitive and difficult to grasp. Some popularized biases in judgment underscore the idea that statistical thinking may be overshadowed by narratives. Just to name two of them:

- Identifiable Victim: People are more likely to donate money with the goal of supporting a single suffering person than they are to donate money for a large group of people suffering from the effects of, say, a natural disaster.

- Base Rate Neglect: When deciding what group/category something belongs in, people lean too much on the qualitative characteristics of the object or person rather than on population-level information (think of the now-famous Linda experiment popularized by behavioral economics, which illustrates this phenomenon; Allen et al. 2006).

These replicable phenomena seem to suggest that quantitative information is somehow less accessible to people when they are forming judgments and making decisions.

Despite this, it is also clear that with a bit of work, people can become extremely data-literate and use it to make better decisions (Sedlmeier, 2002). Among the physicians who participate in our market research, there is a verbal deference to data that is at least partly driven by their academic training and community culture. There are also plenty of instances where numeric evaluation of options is straight-forward, as is the case when one product can boast efficacy with 20% of users and another boasts 40%. Still, it is also clear that most people need some degree of training to interpret many of the forms of data that we use in persuasive communication.

In contrast, stories have a gravity-like quality to them. They invite us into the lives of others and allow us to visualize ourselves having similar experiences. Some psychologists suggest that the stories persuade primarily by evoking emotions, while others suggest that stories allow us to conduct more complete mental explorations of possible actions before we make decisions. Many researchers in the field of evolutionary psychology argue that storytelling has been a key to the success of our species (see Ferretti, 2022, or the popular book Sapiens by Yuval Noah Harrari). For our purposes, the precise reason why stories are more captivating than numbers matters less than the simple fact that they are.

With these basic ideas in mind, let’s see what the accumulated data tell us about the relative power of communications that use data or personal stories and anecdotes to make their persuasive case. To be clear, when we use the term “narrative” in the context of examining persuasive communication, we are referring to communication that use personal stories, testimonials, or anecdotes to convey their essential points. This typically means that the communication features one or more characters, a plot and a story arc that includes a resolution (see discussion by Shen et al, 2015 for a nice overview of narrative communication in healthcare).

The Surprising Truth: Data Usually Wins Over Narratives

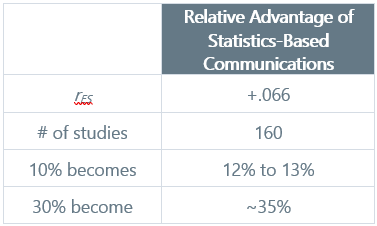

I confess this one surprised me, and reminds me of how useful it is to have a large base of evidence to use when trying to understand a phenomenon. In the largest meta-analysis to-date on this topic, Freling et al (2020) examined results from 160 individual experimental comparisons totaling more than 30,000 participants looking at the persuasive impact of communications that emphasized statistics/data vs. communications that featured narratives about individuals. They found that communications that adduce statistical evidence are more potent at changing downstream marketing-relevant endpoints compared with communications emphasizing narratives. The total effect is modest and roughly equivalent to the effect of generic population-level healthcare messaging when compared to control conditions.

Table 1. Incremental Persuasive Power of Statistics-Based Communication over Narrative-Based Communication

As we would expect based on our prior examination of communication effects, the researchers also found no differences in the effects across outcome measures. That is, attitudes, beliefs and behavioral intentions are all effected to the same degree by statistics relative to anecdotes. This is a nice illustration of why paying attention to evidence is so important.

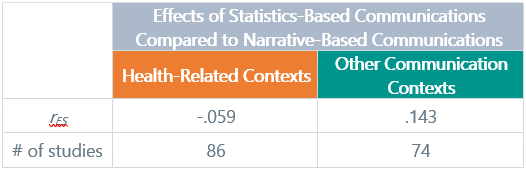

But As Usual, Healthcare is Different

We’ve noted in several of our posts that the world of healthcare is simply different when it comes to persuasive communication, and here we get to illuminate yet another example – this time with a healthy dose of irony. There were several major moderators to the above-referenced meta-analytic effects on the relative persuasive power of data. Using meta-analytic regression, the authors found a cluster of situations where stories/narratives about individuals are more persuasive than statistics and data. These are:

- Health-Related Behaviors: Studies that were concerned with healthcare or health-related behavior

- Severe Threats: Studies involving scenarios and decisions with frightening or consequential outcomes

- Impact on the Self vs. Impact on Others: Studies that involved making decisions for oneself versus making decisions for other people (e.g., children, patients)

You may be making the connection between these three variables already. Situations that provoke strong emotions and visceral conceptualization of future outcomes are less influenced by cold hard facts. And, quite naturally, humans struggle with objectivity when the issues at hand concern their own lives, bodies, and health (versus someone else’s). Healthcare is, rather obviously, concerned with threats to life and functionality. It is this precise setting, where objectivity and data would seem most helpful and important, that we lean most heavily on narrative to guide our decisions. We might say that it is precisely when we need to be most attentive to data that our tendency to lean on anecdotes really kicks in. These findings also underscore part of the value of having physician playing the role of educated advisors.

Table 2. Story-Based Communication Beats Statistics-Driven Communication in Health Settings

Before moving on, I will note that a separate meta-analysis was published a few years later that replicated the above effects (see Xu, 2023). In this case, the author examined health-narrative effects exclusively, meta-analyzing k=65 experiments with over 13,000 participants where the communications were exclusively focused on health-related decisions and scenarios. They found that narrative-driven communications were more persuasive for prevention-related behaviors.

Can’t You Just Combine Them?

Of course, persuasive communications could (and often do) simply integrate data against the backdrop of individual anecdotes. And one might assume that the effects of such integrations would be additive relative to persuasive power. Interestingly, Hornikx (2018) found through experiments on persuasive claims using combinations of statistical and anecdotal evidence that only certain individuals can make the conceptual connection between a single anecdote and a statistic characterizing the same phenomenon. Overall, his work showed very little evidence for an additive effect of stacking data on top of stories or stories on top of data.

What Does a Good Story Buy You?

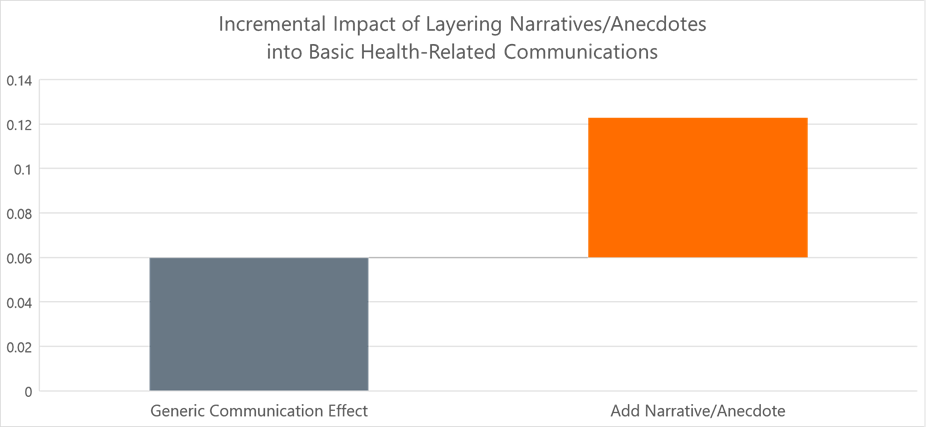

To round out this post, let’s look at the absolute lift that comes with narrative-based persuasive communications when they are applied to the world of healthcare. A 2015 meta-analysis by Shen et al examined the persuasive power that comes with adding narratives to basic health-related communications (i.e., communications that were non-narrative). The 34 included experiments compared narrative-based communications (e.g., vignettes about individual patient success stories or personal tragedies) to more conventional communication statements. They found an absolute effect-size difference of r=+.063. In Figure 1 below, we show this incremental difference relative to the conventional, generic healthcare communication effect size as it relates to behavior change (i.e., ~r=.06).

Figure 1. Incremental Power of Narrative-Based Communication in Healthcare

NOTE: The 2020 meta-analysis by Freling et al was specifically focused on comparing statistics-based communications against anecdote/narrative-based communication, so it does not allow us to isolate the incremental effect of one or the other relative to general/generic communications. Hence, our additional consideration of the Shen et al study.

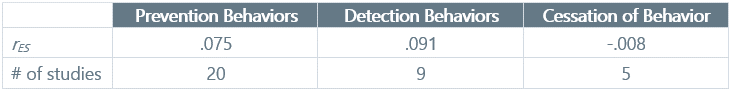

The authors also conducted separate analyses for different kinds of healthcare behaviors – specifically looking at behaviors that were prevention-focused, detection-focused (i.e., related to screening) and cessation focused (e.g., smoking, alcohol). Consistent with our own prior analysis dealing with communication differences with specific types of behavior, they found that narratives perform similarly for prevention- and detection-based behaviors but have essentially no impact on behavior cessation. Note that with cessation, the total number of contributing studies was modest and should be seen as more directional.

Table 3. Story-Based Communication Effects on Diverse Health Behavior Outcomes

Readers interested in learning more about how different types of complex health-related behavior respond to persuasive communication may find value in our post entitled, “Are Some Health Behaviors Harder to Shape with Marketing?”

Finally, Shen et al also point out a few other useful moderating effects. First, the effects of narrative-based communication are about equal for attitudes, intentions and behaviors (which should no longer be a surprise). Second, narrative-based communications seem to work more effectively in video form than in print form, though the difference is not enormous. Third, narrative communications violate the KISS principle: They are more persuasive when they are longer and more detailed. This runs in contrast to the clear findings from text-based communications, where shorter messages are more powerful than longer ones (see Joyal-Desmarais et al, 2022).

Take-Home Points

There are a handful of practical conclusions to take away from this summary.

- On balance (and ironically), in the context of healthcare communications, vignettes characterizing personal stories and individual narratives about the benefits or risks of specific behaviors are likely to be more effective at changing hearts, minds and behavior with patients.

- The greater the degree of risk or threat associated with the condition in question, the more likely a narrative-based communication is to lead to downstream changes in attitudes, intentions, and behaviors.

- Using narrative-based communication in healthcare buys you twice the impact of general population communications. Further, narrative effects may be modestly enhanced by using video as the delivery medium.

- However, when people are making decisions for others, as is the case with physician-patient relationships, data-based communication will be more persuasive in most cases.

- Finally, remember that there are segments of humans who, by dint of training or natural cognitive style, will be more responsive to data-based communication.

For marketers and insights professionals, the findings we have summarized here may seem obvious and mostly aligned to the general practices in our industry. However, at a minimum, it may be helpful to know that what we are doing is aligned to the best evidence we have about what works in persuasive communication.

If You Enjoyed These Points, You Might Also Like: When we think about the return on investment for marketing spend, one of the major considerations is which type of media to concentrate on. Different audiences use different media channels and platforms to different degrees, and we all have the sense that some are more effective than others. But were you aware that the effectiveness of different media can be quantified in terms of the relative power they offer in terms of changing customer behavior? To see the evidence, check out our post entitled, “How Much Does Media & Channel Selection Matter in Healthcare Communications?”

To learn more, contact us at info@euplexus.com.

About euPlexus

We are a team of life science insights veterans dedicated to amplifying life science marketing through evidence-based tools. One of our core values is to bring integrated, up-to-date perspectives on marketing-relevant science to our clients and the broader industry.

References

Allen, M., Preiss, R. W., & Gayle, B. M. (2006). Meta-analytic examination of the base-rate fallacy. Communication Research Reports, 23(1), 45-51.

Ferretti, F. (2022). Narrative persuasion. A cognitive perspective on language evolution (Vol. 7). Springer Nature.

Freling, T. H., Yang, Z., Saini, R., Itani, O. S., & Abualsamh, R. R. (2020). When poignant stories outweigh cold hard facts: A meta-analysis of the anecdotal bias. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 160, 51-67.

Hornikx, J. (2018). Combining anecdotal and statistical evidence in real-life discourse: Comprehension and persuasiveness. Discourse Processes, 55(3), 324-336.

Joyal-Desmarais, K., Scharmer, A. K., Madzelan, M. K., See, J. V., Rothman, A. J., & Snyder, M. (2022). Appealing to motivation to change attitudes, intentions, and behavior: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 702 experimental tests of the effects of motivational message matching on persuasion. Psychological Bulletin, 148(7-8), 465.

Sedlmeier, P. (2002, July). Improving statistical reasoning by using the right representational format. In Proceedings of the Sixth International Conference on Teaching Statistics.

Shen, F., Sheer, V. C., & Li, R. (2015). Impact of narratives on persuasion in health communication: A meta-analysis. Journal of advertising, 44(2), 105-113.

Xu, J. (2023). A meta-analysis comparing the effectiveness of narrative vs. statistical evidence: Health vs. non-health contexts. Health Communication, 38(14), 3113-3123.

Winterbottom, A., Bekker, H. L., Conner, M., & Mooney, A. (2008). Does narrative information bias individual’s decision making? A systematic review. Social science & medicine, 67(12), 2079-2088.