Table of Contents

- Complex Views on Fear-Based Messaging

- What Kind of Reaction Can We Expect from Fear-Based Communication?

- Making Fear-Based Communications More Positive

- Can We Go Too Far With Fear?

- Take-Home Points

Complex Views on Fear-Based Messaging

In my conversations with life science marketing professionals over the years, I have observed that people have complicated feelings about campaigns that use elicited fear as a way to activate customer behavior. Some people seem to regard it as manipulative or Machiavellian. Others see it as distasteful or dark – perhaps similar to the way they regard fear-based political advertising. Some worry that fear-based campaigns often seem to carry a degree of hyperbole relative to the true nature of the risk being characterized. And some worry that these kinds of messages simply result in customers “shutting down” or repressing the information because it is frightening. There is certainly evidence that fear-based messaging can be dismissed or produce avoidance responses (e.g., “This is just too scary to think about” – see Witte and Allen, (2000)). Nevertheless, fear-based communications abound in life science for a simple reason: They work.

Research on the use of fear for persuasion has been highly active in public health and psychology settings since about 1950 and features literally hundreds of correlational and experimental studies. The first published meta-analysis on the subject appeared in 1984, and since the millennium, this accumulated literature has given us impressively robust and specific insights into how these interventions translate to different cognitive and behavioral outcomes. This post will summarize what we know about how to use fear-based communications effectively. While we take no position on the ethics or optics of this style of messaging, we do offer some suggestions for framing fear in productive and positive ways.

NOTE TO THE READER:

To limit the length of this post, we are intentionally side-stepping any discussion of the physiological, neurochemical or measurement considerations that come with studies of fear as an experienced emotion, because these are large subjects that come with their own large scientific literatures. Instead, we will begin from the place where a human is experiencing some kind of subjective fear response after being exposed to some kind of health-related communication that conveys information about a health risk.

What Kinds of Reaction Can We Expect from Fear-Based Communication?

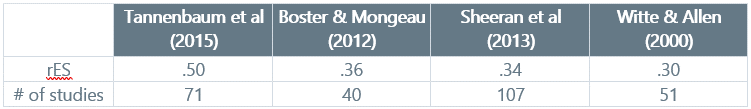

A reasonable starting point for our analysis might be to ask ourselves if fear-based communications actually produce a fear reaction (as compared with indifference, annoyance, or some other emotional response). Several meta-analyses test for this “manipulation check” by looking at the subjectively reported emotional responses. Table 1 shows meta-analytic confirmation of these basic effects published at various points in time since the year 2000. Without exception, these analyses indicate that the average recipient experiences a modest change in their emotional state. Naturally, these effects tend to be fairly modest. Most healthcare risks are relatively abstract and may also be experienced as psychologically distant (as in, occurring far into the future), so we would expect the response to be limited. But the data clearly indicate that these manipulations promote a feeling of disquiet, anxiety or even alarm.

Table 1. Magnitude of Subjective Fear Response to Fear-Based Communications

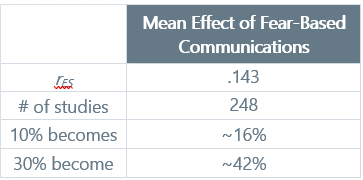

Next, we would want to confirm that fear-based communications have a net effect on marketing-relevant endpoints, which would typically include attitudes, intentions and actual behavior change. A meta-analysis from 2015 in Psychological Bulletin (one of the flagship journals of the field) sets the table for this discussion. The researchers looked at the impact of the fear communications on a range of expected endpoints: attitudes toward the behavior, intentions and actual behavior change. The mean effect size was .143, which is small by statistical convention, but solid relative to typical effects seen in healthcare communications. As the authors noted, fear-based manipulations are effective in shaping attitudes and behaviors in the vast majority of circumstances. So, there’s something in these effects that we have to take seriously.

Table 2. Effects of Exposure to Fear-Based Persuasive Communications

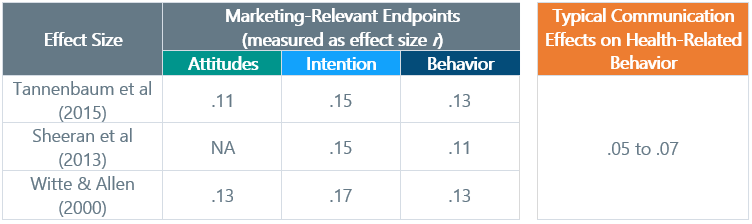

In a prior post entitled, “Persuasive Communications Can Shape Any Endpoint that Matters to Marketers”, we showed that messaging effects tend to be relatively similar across major endpoints that marketers care about. The same is true for studies of fear-based communication. Table 3 below shows the results from three separate meta-analyses published between 2000 and 2015 that examined how fear-based communications differentially influenced attitudes, intentions (i.e., planned behaviors) and observed behaviors. The included experiments come almost exclusively from the world of healthcare. Along with confirming what we would expect – that fear-based manipulations work against all three relevant endpoints – it is worth appreciating the consistency of effects across the meta-analyses. This kind of consistency underscores the learning power that comes with our maturing domains of marketing-relevant science. To provide additional context, we have included a final column in Table 3 below which shows the ordinary effect of generic health-related communications on downstream behavior.

Table 3. Effects of Fear-Based Persuasive Communications on Diverse Marketing Endpoints

By way of comparison, we can re-visit the standard tailored communication effects that we see in healthcare settings. Fear-inducing communications produce about twice the effect of other tailored communications.

The accumulated evidence also suggests a number of “tune-ups” to fear-based communication of which marketers should be aware.

- Emphasize Susceptibility:

- Communications that emphasize risk or personal susceptibility are more persuasive than those that simple articulate the presence of a health risk. Inclusion of statistics on susceptibility make fear-based communications about twice as effective in terms of downstream behavior change.

- This example is adapted from a published experiment: “One in fourteen women will develop breast cancer during her life. So every woman may get breast cancer. You also run that risk!”

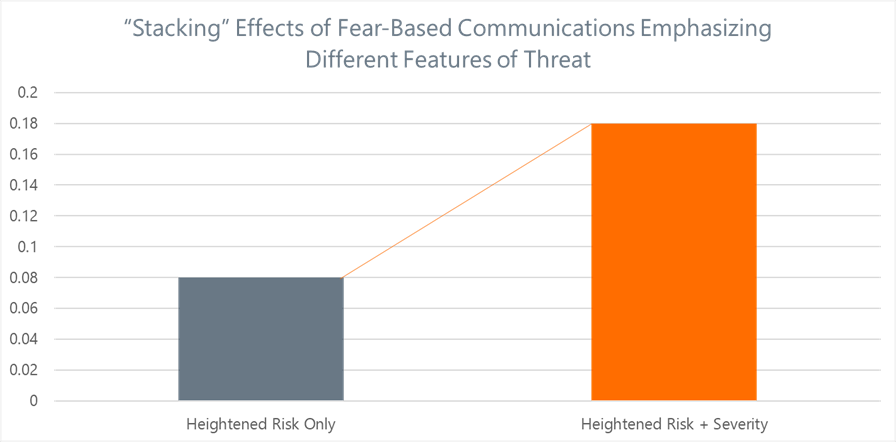

- Stacking Severity & Susceptibility:

- In their meta-analysis focusing exclusively on formal experimental manipulations of fear-based communication, Sheeran et al (2013) demonstrated that communications had larger downstream effects on behavior when they emphasized both the susceptibility (i.e., personal risk; likelihood) and severity of the outcomes. Severity can be emphasized by focusing on visceral aspects of a condition (e.g., loss of vision, loss of limbs, organ failure, death, etc.).

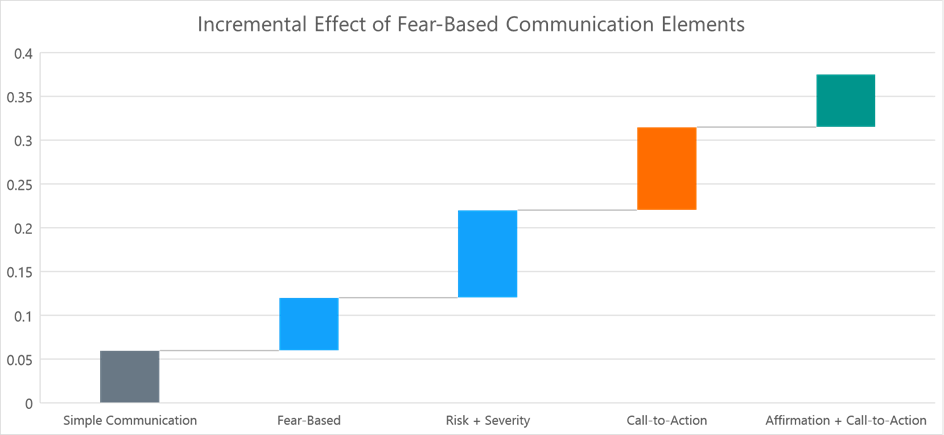

- Figure 1 below illustrates the impressive additive effect of combining these elements.

- Don’t Water Down the Threat:

- Communications that try for a more gentle tone when conveying risk (e.g., “You may be at risk for…”) are substantially less effective than communications that state the nature of health threats more bluntly. This was found in the Witte and Allen analysis in 2000 and replicated later by Tannenbaum et al in 2015.

Figure 1. Differences in Effect on Behavior from “Stacking” Multiple Dimensions of Fear-Based Communication

Taken together, these tuning effects can have a substantial incremental impact on downstream behavior change.

Making Fear-Based Communications More Positive

While the outcomes we have discussed so far should be persuasive (because the evidence is pretty overwhelming), we might be left feeling a bit conflicted. Is the answer to marketing simply to make all messaging negative and threat-centric? Isn’t there some way to encourage productive behavior change that is more optimistic? Happily, the answer is yes.

In a previous post, we described the interesting phenomenon of increasing peoples’ sense of self-determination through the use of affirming messages. There is an interesting point of intersection between that idea and our current discussion of fear. It turns out that fear appeal is most effective when it comes with a productive “escape hatch” in the form of what academics call an efficacy statement. Researchers who have explored these communication effects classify two avenues for efficacy statements.

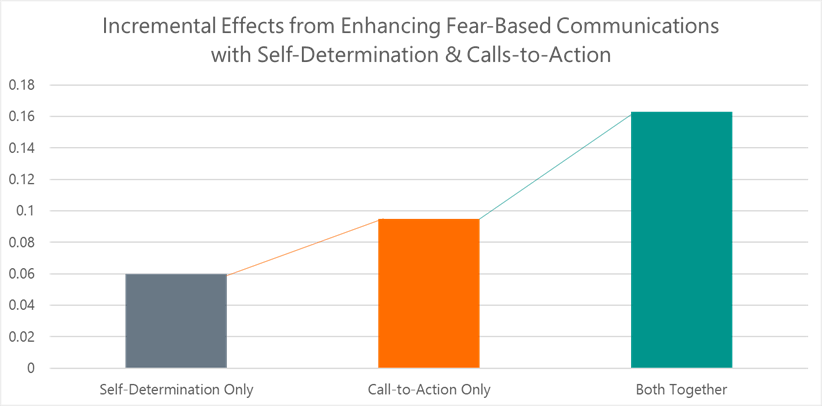

- Self-Determination: Affirmation that you can do something about the problem that has been highlighted by the fear-inducing communication

- Clear Call-to-Action: Providing a clear behavioral call-to-action by articulating one or more specific steps that the recipient can take to mitigate risk

This makes sense based on what we’ve learned previously about self-determination. People need to believe they can make a difference in their own health and they need guidance on precisely what that change should look like. Enhancing communications with these additional features not only re-frames the message to make it more productive and action-oriented, but it also has a substantial effect on behavior. Figure 2 below shows the incremental effects on behavior change that stem from adding these positive and affirming features to communications that are foundationally about fear. The important thing to keep in mind is that these effects are on top of what you would get from a well-constructed fear-based communication. These data come from the Sheeran et al (2013) meta-analysis, which synthesized data from 93 independent experiments using fear-based manipulations.

Figure 2. The Additive Benefits of Enhancing Fear-Based Communication by Emphasizing Affirmation and Calls-to-Action

As a side note, a 2022 meta-analysis by Bigsby and Albarracin reinforces that the call-to-action is likely to be the more important of these two considerations.

Let’s take a look at the integration of these communication elements so we can see how the pieces fit together to give us more powerful communications. Figure 3 below shows the plausible stepwise change in the meta-analytic effect on behavior from experimentally manipulated tests of messaging elements. The incremental effects are built from the foundation of basic healthcare messaging effects (as described in our previous posts, including “Why We Can’t Expect the Same Level of Impact from Healthcare Messaging”), which we know is about .06. Readers can see a similar analysis in the Sheeran et al meta-analysis, as well as a comparative analysis in the 2022 Bigsby and Albarracin analysis. My synthesis below is actually more conservative, arriving at a total plausible effect size of .37 compared with .45 as reported by Sheeran et al. It also aligns precisely to the effects reported in the 2022 meta-analysis by Bigsby and Albarracin.

Figure 3. Stacking Effective Elements of Fear-Centric Communications to Increase Downstream Effects on Behavior

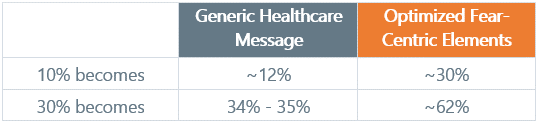

To put this all in context, we can translate these accumulated behavior-change effects from the traditional effect size, r, into our more practical “bodies-moved index.” This conversion is shown in Table 4 and probably does not require further explanation.

Table 4. Evaluating Stacked Fear-Centric Messages vs. Generic Healthcare Messages

Can We Go Too Far With Fear?

Marketers might sensibly worry that they can go too far with fear-based communications because they may create a range of unintended non-productive reactions, which could include recipients minimizing the issue, developing counter-arguments, denying their own susceptibility or simply “shutting down” with respect to the issue or behavior in question. Researchers refer to these unproductive outcomes as defensive responses. The Witte and Allen (2000) meta-analysis looked at this issue systematically. Their findings are fascinating. Fear-based manipulations did produce defensive response effects. But at the same time, the kinds of behavior-change responses we have been focusing on also emerged in the same studies. The way to resolve this seemingly confounding effect is simple: Some humans respond productively and others respond unproductively. Given the sheer scope of potential positive change that can result from appropriately-structured fear-based communications, it may be that marketers need to accept some degree of “collateral damage.”

Another angle on this question concerns the intensity of the fear-based manipulation. Is it possible to be too “over the top” with our fear-based communications? The data suggest not. Tannenbaum et al’s meta-analysis looked at communication experiments that had used multiple levels of fear intensity. After computing the effects for all fear-levels, they tested for the “inverted U” pattern that would be implied if some fear manipulations were too intense. They found no evidence for that pattern, but instead determined that moderate and high degrees of fear manipulation produced similar effects (both more effective than “mild” or gentle fear manipulations). So based on the evidence, we don’t need to worry about over-dramatizing or hyperbolizing effects, but we also shouldn’t expect them to be more effective than a moderate, reasoned approach to communicating health risks.

Take-Home Points

Whatever your personal views on the use of fear in healthcare communication, it is worth internalizing the very clear evidence about how this style of communication relates to behavior change. This approach simply carries a lot of persuasive power. More specifically:

- POINT #1: In terms of downstream behavior change, you can expect fear-inducing communications to produce about twice the effect of standard tailored messages

- POINT #2: Communications that articulate personal risk or susceptibility are more effective

- POINT #3: Communications that also present the severity of potential negative outcomes have even larger effects when paired with personal risks

- POINT #4: Perhaps most importantly, communications should give the recipient a clear call to action – a step they can take to mitigate the risk – and should affirm their capacity to make a change in their own health

When we wrap all these communication elements together, we not only elevate the persuasive power of our messages by several times, we also reframe our communications to make them more positive, upbeat and inspiring to recipients. By balancing fear with productive ballast, we may be able to reconcile any outstanding misgiving we might have about appealing to fear in the first place.

If You Enjoyed These Points, You Might Also Like: One of the things that excites us about the scientific study of communication strategies is that we can now confidently say that messaging can have precise effects on almost any aspect of the behavior change cascade. From changing how customers feel about a product, to changing their overt behavior, we can now gauge the effects of our campaigns with reasonable precision. This is great news for marketers, who often have very precise, intentional outcomes in mind when they create a campaign. To see the evidence, check out our post entitled, “Persuasive Communications Can Shape Any Endpoint that Matters to Marketers”.

To learn more, contact us at info@euplexus.com.

About euPlexus

We are a team of life science insights veterans dedicated to amplifying life science marketing through evidence-based tools. One of our core values is to bring integrated, up-to-date perspectives on marketing-relevant science to our clients and the broader industry.

References

Bigsby, E., & Albarracín, D. (2022). Self-and response efficacy information in fear appeals: A meta-analysis. Journal of Communication, 72(2), 241-263.

Boster, F. J., & Mongeau, P. (2012). Fear-arousing persuasive messages. In Communication yearbook 8 (pp. 330-375). Routledge.

Sheeran, P., Harris, P. R., & Epton, T. (2014). Does heightening risk appraisals change people’s intentions and behavior? A meta-analysis of experimental studies. Psychological bulletin, 140(2), 511.

Tannenbaum, M. B., Hepler, J., Zimmerman, R. S., Saul, L., Jacobs, S., Wilson, K., & Albarracín, D. (2015). Appealing to fear: A meta-analysis of fear appeal effectiveness and theories. Psychological bulletin, 141(6), 1178.

Witte, K., & Allen, M. (2000). A meta-analysis of fear appeals: Implications for effective public health campaigns. Health education & behavior, 27(5), 591-615.