Table of Contents

- Introduction

- What is Communication-Tailoring?

- A Fun Example

- Is the Juice From Tailoring Worth the Squeeze?

- What About Tailoring to Demographics?

- Summing Up

Introduction

So far this series of posts about the science of persuasive communication has focused on some of what we think of as the “nuts and bolts” of campaign planning. We’ve covered topics like how much behavior change you can realistically expect to achieve with your customers, how long those effects last, and the different effects associated with your choice of media channel. Beginning with this piece, we are going to take a turn toward ways of leveling up our communication effects through the alignment of content to specific elements of customers’ mental lives. We’ll make the case that communicating based on knowledge of customer motivations and dispositions is very much in the best interest of brands who want to positively influence customer behavior.

In this short summary, we’ll open this topic by looking at:

- What we mean by tailoring communications to align with customer mentality

- What kind of effects can we expect for our efforts

In later posts, we’ll unpack specific types of communication techniques to give marketers and insights professionals ideas about how to leverage the power of tailoring for themselves.

What is Communication-Tailoring?

Researchers who devote their careers to the study of persuasive communication have landed on the term communication-tailoring to describe the idea of aligning content to customer psychology (Noar et al, 2009). Related terms like motivation matching and targeting are worth being aware of, but for the purposes of our discussion, we will use the term tailoring. In practice, tailoring has come to mean aligning specific content (data, ideas, images) to customers who have distinct needs, motivations or other psychological characteristics. From a process standpoint, this necessitates that we first learn something about specific characteristics of the individual customer’s motivations or dispositions, and then creative communication content accordingly.

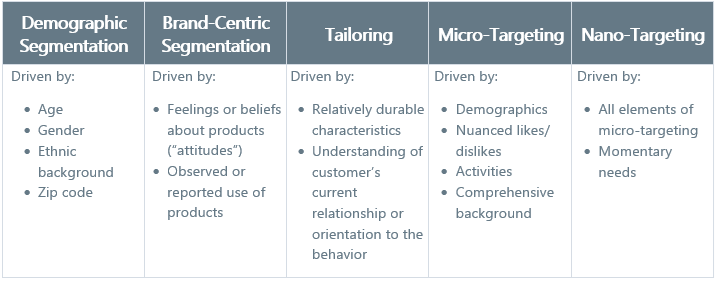

In reading this, if you immediately think of segmentation, you are getting the idea. In actual practice (and in experimental studies), tailoring amounts to a form of customer segmentation or stratification. However, it is distinct from some traditional modes of segmentation that focus on (a) customer demographics, and (b) brand-centric segmentation, which deal with how customer use products, or think/feel about them. Tailoring is about the innate and internal characteristics of the recipient, rather than characteristics of a broad cohort. In my opinion, the concept lies somewhere in between the traditional notion of market segmentation and the contemporary practices of micro- and nano-targeting (see, e.g.,Chouaki et al, 2022), which are truly executed at the individual level. The reason is that while our exploration of customer psychology could hypothetically produce an infinite number of distinct orientations, the practical reality is that motivational and dispositional characteristics that matter for marketing tend to organize themselves into a workable number of groups. I would add that this is probably most realistic for life science marketers and salespeople.

Table 1. Where Communication-Tailoring Fits in the World of Customer Targeting

I occasionally encounter resistance to the idea of communication tailoring at the level of customer psychology, in part because I believe some marketers doubt that this can be done practically or affordably, or because they are skeptics about psychology in general. But the reality is that you don’t always need to use a complex or expensive data-gathering process to leverage psychological tailoring, as we’ll show in the next example.

A Fun Example

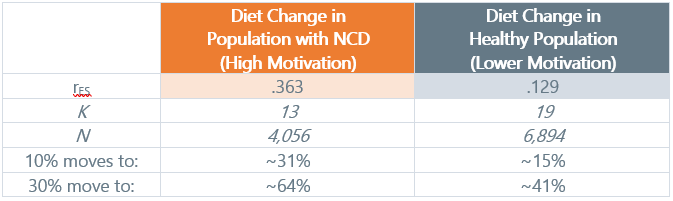

A simple illustration of how easy and powerful tailoring can be comes from comparing the results of several recent meta-analyses. Both meta-analyses examined eHealth communication interventions on diet – specifically targeting an increase in fruit/vegetable consumption. The first analysis by Duan et al (2021) focuses on populations of people diagnosed with what they characterize as non-communicable diseases (NCD), which, in the individual studies, mostly relate to cardiometabolic conditions, such as Type II diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, etc. The second analysis by Rodriguez-Rocha and Kim (2019) focuses on healthy populations. The mix of interventions used in the included studies is similar for both analytic groupings. What we see is that the behavior change effect size is virtually three times larger in the NCD populations compared to the healthy populations. This difference is explicitly noted by Duan et al, who attribute it to the underlying psychological urgency of being formally diagnosed with conditions that are known to be mediated by diet. I agree with their assessment.

Table 2. Comparing the Effectiveness of Messaging Campaigns on Diet in Differently-Motivated Populations

I like this example because we didn’t have to do anything elaborate to evaluate the underlying motivation of these groups. For marketers, the main thing to realize is that developing the instinct to consider the psychological state of customers can help you to anticipate how they evaluate the value and cost of engaging in a particular health-related behavior. Not only does this make us better marketers in general, but it also can help us anticipate what we can achieve in messaging campaigns.

Is the Juice from Communication Tailoring Worth the Squeeze?

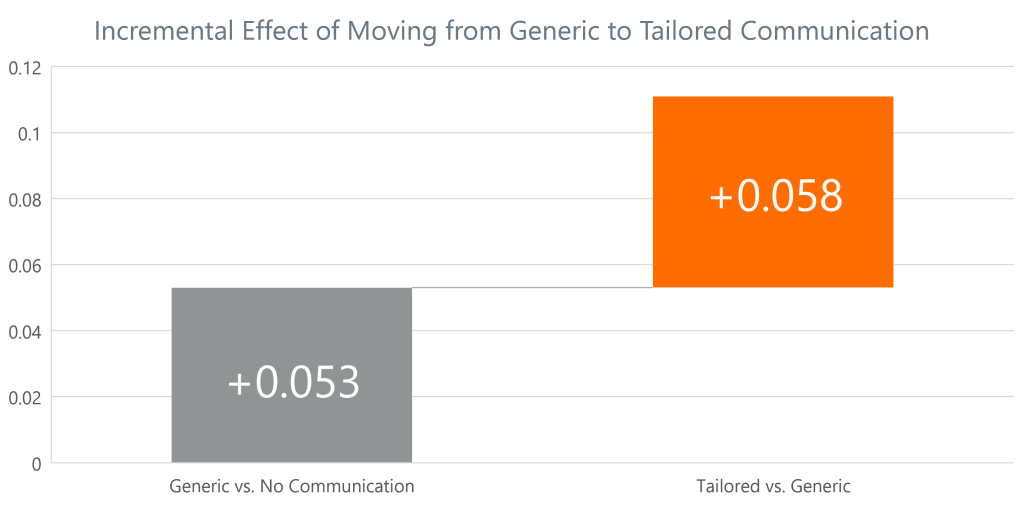

Yes. To set the table for some of the impressive findings on communication effects using tailoring, let’s remember that, on balance, the rough average effect size measuring communication effects on health-related behavior change is about r=.05 to .07 (see several of our prior posts for further details). To put that number in context, if 30% of your customers were already engaging in the desired behavior prior to your campaign, you could expect a non-tailored communication to move that number to about 35%. That’s not a bad outcome, but in many cases, we’ll want to do better.

We’ve referenced a wonderful meta-analysis by Noar et al from 2007 on several occasions. This synthesis of 58 communication experiments is a boon because it focuses only on healthcare behavior change, while examining a range of different behavioral outcomes. In this sense, it allows us to draw broad conclusions about promotional effects in life science communication. If there is a limitation to this study, it is in the fact that the researchers looked only at print-based communications because as we saw in our post on media and channel effects, print is a relatively weak vehicle for persuasive communication. In Figure 1, we show their core findings which compare tailored communications to generic communications, and conditions where people received no communication. The “Difference” column can be thought of as an estimate of the effectiveness of generic communications, which aligns almost perfectly with the r=.06 cited above. The key take-away from this analysis is:

- You get a roughly 100% lift in behavior change from using tailored communications.

Sounds pretty worthwhile to me.

Figure 1. Incremental Effect of Moving from Generic to Tailored Communications

The studies in the Noar et al analysis focus on some relatively straight-forward aspects of tailoring. For example, some include assessments of ingoing attitudes toward the health behavior in question, or assessments of the person’s behavioral baseline.

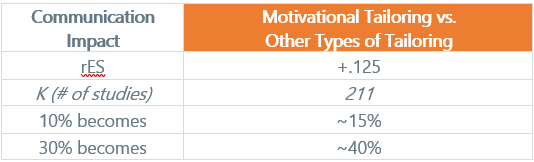

A 2022 meta-analysis of experimental assessments of message tailoring by Joyal-Desmarais et al helps us see even greater potential in tailoring our communications. Compared to the Noar et al findings, this more recent study showed larger overall effects. However, in their analysis they only included experiments that used tailoring in more sophisticated ways related to explicit motivational matching. In practical terms, this means the included experiments were focused on more rich, nuanced aspects of customer psychology – including facets like cognition, culture and values, as well as practical needs that arise in specific life and work settings. The meta-analysis encompasses effects in a range of domains, but the piece we care about is the targeted analysis of healthcare-based experiments yielded a total rES of .125, which (as the authors note) is explicitly incremental to the effects of other persuasive communication techniques. This is analogous to how the Noar et al study compared tailoring to generic messaging. However, the incremental effect size they achieve is sharply higher than what Noar et al found: Essentially these more nuanced types of tailoring had roughly 2x the impact on behavior change compared with the earlier analysis.

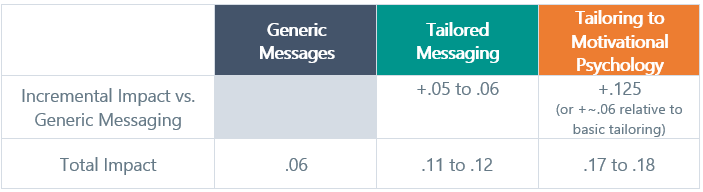

Table 3. Meta-analytic Effects of Motivational Tailoring

There is one other useful structural feature of the 2022 analysis that is worth pointing out. All of the effect sizes were computed relative to the performance of a comparison condition that also involved formal communication manipulations. Naturally, every control condition is a bit different, but on balance, it is reasonable to assume that they would be no less effective than generic communication effects in healthcare, which we know to be ~r=.06. This allows us to draw some simple conclusions about the incremental value of different levels of tailoring, which we summarize in Table 4 below.

Table 4. How to Think About the Relative Value of Communication-Tailoring Approaches

- Conclusion: It is not unreasonable to expect that tailoring your communications to deeper, motivation-level aspects of customer psychology can yield a behavior change effect that is about 3x what you would achieve with a general population campaign.

Even if we “discount” these effects to account for the fact that they are all based on controlled studies, we believe that the investment value of tailoring is apparent.

What About Tailoring on Demographics?

As we wrap up, I want to take a moment to draw an important distinction. When we speak about tailoring, we are really focused on characteristics of the individual rather than the characteristics of large groups of people, which is what we mean when we talk about communicating based on demographics. However, some tailoring experiments definitely use demographic factors as part of their tailoring process. The core limitation of demographics is that we all intuitively realize that those variables have a tenuous relationship with many of the behaviors that we would actually want to change. Does living in a rural area really cause obesity? Does being a male cause you to be less adherent in pill-taking? We don’t need to dig into a textbook to know that there are deeper mechanisms at play. This is underscored in the Noar et al meta-analysis. When they isolated the effects of tailored messages on demographic groups based on age, biological sex and ethnicity (defined very broadly), all of the effects were near-zero and not statistically significant. Two exceptions were a very small directional tilt toward lower communication effectiveness among samples with more females, and larger effects outside of the United States. Both these modest trends were replicated by Joyal-Desmarais et al analysis.

A 2013 meta-analysis by Lustria et al focused on web-based tailored communication effectiveness. This study also included an analysis of demographic variables and came to similar null or near-null conclusions. The same is true for the Krebs et al (2010) meta-analysis of healthcare messaging effectiveness, which showed minimal relationships between demographic variables and message sensitivity. By the numbers, tailoring or segmenting for communication based on demographic variables is not very effective in healthcare settings.

Note that demographic tailoring and tailoring to a customer’s cultural background are not the same thing. Aligning communication to the underlying culture of a recipient group does appear to have some promise, and this warrants its own full-length discussion. Culture encompasses a much richer tapestry of ideas, including values and motivations, and these are precisely the dimensions that are absent from most demographic characteristics. We will explore culture-matching effects in a separate post.

Summing Up

Marketers who make the effort to identify specific aspects of customer psychology that are linked to behavior change and then customize communications based on these motivational characteristics will be substantially rewarded. It is perfectly realistic to expect a 2x to 3x lift in your campaign effectiveness depending upon how nuanced/precise your tailoring efforts are.

Relevant Topic: In our posts titled “Leveraging Customer Psychology for Powerful Communications – Part 1: Communicating to Strengthen Self-Determination” and “Part 2: Fear as a Lever for Behavior Change“, we unpack this topic further by talking about some of the precise examples of customer psychology that appear to be most effective for leveraging in our campaign development.

To learn more, contact us at info@euplexus.com.

About euPlexus

We are a team of life science insights veterans dedicated to amplifying life science marketing through evidence-based tools. One of our core values is to bring integrated, up-to-date perspectives on marketing-relevant science to our clients and the broader industry.

References

Barbu, O. (2014). Advertising, microtargeting and social media. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 163, 44-49.

Chouaki, S., Bouzenia, I., Goga, O., & Roussillon, B. (2022). Exploring the Online Micro-targeting Practices of Small, Medium, and Large Businesses. Proceedings of the ACM on Human-Computer Interaction, 6(CSCW2), 1-23.

Joyal-Desmarais, K., Scharmer, A. K., Madzelan, M. K., See, J. V., Rothman, A. J., & Snyder, M. (2022). Appealing to motivation to change attitudes, intentions, and behavior: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 702 experimental tests of the effects of motivational message matching on persuasion. Psychological Bulletin, 148(7-8), 465.

Krebs, P., Prochaska, J. O., & Rossi, J. S. (2010). A meta-analysis of computer-tailored interventions for health behavior change. Preventive medicine, 51(3-4), 214-221.

Lustria, M. L. A., Noar, S. M., Cortese, J., Van Stee, S. K., Glueckauf, R. L., & Lee, J. (2013). A meta-analysis of web-delivered tailored health behavior change interventions. Journal of health communication, 18(9), 1039-1069.

Noar, S. M., Benac, C. N., & Harris, M. S. (2007). Does tailoring matter? Meta-analytic review of tailored print health behavior change interventions. Psychological bulletin, 133(4), 673.

Noar, S. M., Harrington, N. G., & Aldrich, R. S. (2009). The role of message tailoring in the development of persuasive health communication messages. Annals of the International Communication Association, 33(1), 73-133.