Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Subtracting is Harder Than Adding

- Is There a Prevention-vs-Detection Distinction?

- Discomfort & Effort Effects

- Take-Home Points

Introduction

We devoted a number of posts to understanding the scope of the effects that marketers can expect to have in changing behaviors, attitudes, beliefs and other endpoints through their communication campaigns. Our goal has been to organize and quantify predictable aspects of communication impact, including issues like domain effects (healthcare vs. consumer), durability of effects and the value of repeated exposure to messages. For this session, we want to talk about a topic that I think does not get sufficient attention in marketing: Are some types of behavior easier or harder to change than others? Understanding this is useful for campaign planning and expectation-setting.

Subtracting is Harder Than Adding

In your own life, have you ever noticed that it is harder to stop doing something you routinely do than it is to start doing something new? We often feel a reluctance to remove things from our lives, whether they are objects, people or routine behaviors because they are part of what psychologists refer to as our endowment (you can read more about this in our post entitled “Why We Can’t Expect the Same Level of Impact from Healthcare Messaging vs. Other Industries”, or the articles by Hubbeling and Jeager et al in our Reference list). Once we experience something, we expect to be able to call upon that experience again in the future.

This dynamic has very significant implications for marketers. If you are using persuasive communication to alter the behavior of a customer population, you can expect an uphill battle if your goal is to get people to do less of something that they routinely do. This will be especially true in the case of behaviors that have addictive characteristics. In contrast, adding new behaviors is more natural.

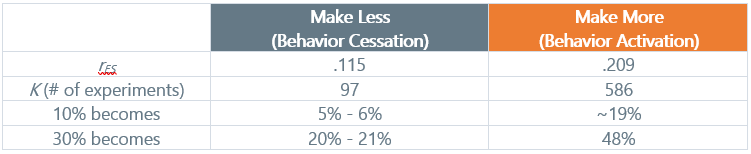

The most recent and generalized evidence on this topic comes from the useful meta-analysis by Joyal-Desmarais et al (2022), which examined message matching effects tested in more than 700 experiments. One of the numerous questions they address is the effect of communications on reducing versus increasing behavior. Their study cuts across a range of domains, including consumer situations, healthcare, and pro-social decision-making. Table 1 summarizes the crystal-clear evidence of a phenomenon that we should all internalize: It is easier to add behavior than to subtract behavior. Based on what we know about the power of endowment, this potent difference in communication effectiveness makes a lot of sense.

Table 1. Generalized Effects of Messaging on Adding/Increasing vs. Subtracting/Decreasing

As you consider their data, keep in mind that their analysis is focused on communication studies that specifically used some kind of message tailoring (aligning content to characteristics of the receiver). That means, by definition, that the effect sizes are going to be larger than what we have typically seen in our prior posts about healthcare communication effects.

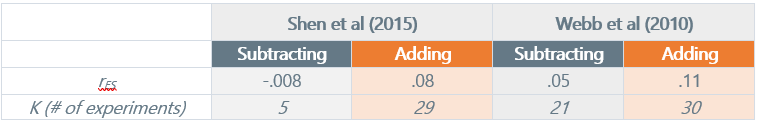

Several healthcare-specific meta-analyses find the same basic pattern “addition vs. subtraction” effects in tests of communication power. A 2015 meta-analysis of persuasive communication effects focusing on narrative-based messaging showed near-zero effects on cessation-related behaviors. Additive behavior change effects were in the normal to slightly-above normal range, likely due to the persuasive power of narrative-based communications. A 2010 healthcare messaging meta-analysis by Webb et al found a similar pattern. Their study looked at persuasive communication delivered via tailored Web-based platforms. Here, the behavior change effects for additive behavior change were essentially 2x those for cessation-related behavior change, which more or less mirrors the effects found by Joyal-Desmarais et al above. It is worth noting that many studies of behavior cessation in healthcare have to do with reduction in the use of addictive substances, such as tobacco and alcohol. So, in this context, the gap in effects is quite reasonable to expect.

Table 2. More Evidence for the Adding vs. Subtracting Effect

- CONCLUSION 1: Persuasive communication can be expected to have approximately 2x the effects on behavior change when we are trying to add new behaviors compared to situations where we want to arrest existing ones.

Is there a Difference in Prevention- vs. Detection-Related Behavior?

In a number of settings, researchers have hypothesized that we would expect to see differences in persuasive communication when comparing behavior change that involves detection (generally meaning screening for disease) versus behavior change that is preventive (see Salovey et al, 2002). This is plausible because the psychology that we associate with these broad categories of health behavior are quite different.

- Detection Behaviors: We might expect that behaviors relating to deliberately discovering disease would be harder to encourage through education or persuasive messages. Many kinds of screening are intimidating because the implications of a positive result may be dire, as in the case of cancer. In a sense, screening behaviors represent a threat to our health endowment. Additionally, information avoidance is also a widely recognized phenomenon in the decision-making literature (see for example the Golman et al review in our Reference list below).

- Prevention Behaviors: The psychology of prevention tends to be different because it generally involves a greater feeling of agency and control. We are taking active steps to prevent something bad from happening, or to expand our health endowment. On the face of it, this more positive psychology might be easier to drive with persuasion compared with detection. However, the range of behaviors that fall into the domain of prevention are also more numerous and varied, which complicates things (think of the difference in pill-taking vs. rigorous exercise).

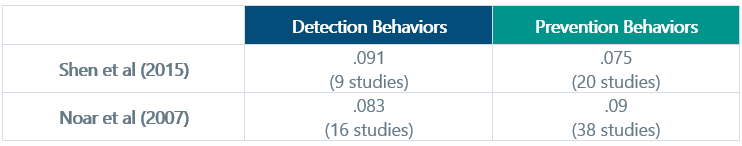

Two meta-analyses addressed this question. The first by Noar et al (2007) focused on print-based communication effects, and the second by Shen et al included studies using a variety of media types but focusing on narrative-based communication. Both studies found nearly identical effects for the prevention-detection delta. This is good news for marketers. You can expect to have equally successful persuasive campaigns whether you are trying to encourage increase screening or an increased rate of some preventive health behavior.

Table 3. Near-Zero Differences in Persuasive Impact on Detection and Prevention Behaviors

We also confirmed this by pulling together a range of reported meta-analytic effect sizes relating to prevention and detection-related behaviors from a diverse set of studies published between 2004 and 2023. We found that communications aimed at increasing detection-related behaviors had an average rES of .074, while prevention-related behavior effects averaged .08.

- CONCLUSION 2: Persuasive communication is about equally effective for promoting health behavior change that relates to disease detection and disease prevention.

Discomfort & Effort Effects

It also stands to reason that some kinds of behavior change are harder to induce through persuasion due to the simple fact that they result in unpleasant outcomes. In psychology and behavioral biology, the evidence in support of reinforcement and punishment effects are diverse and overwhelmingly clear. All other things equal, we do more of what we are rewarded for and we do less of what gets punished. When it comes to healthcare, many changes in behavior result in things that are not especially pleasant. Here are some examples:

- Smoking cessation results in cravings and withdrawal symptoms

- Exercise is inherently uncomfortable for many people

- Some medicines will produce reliable unpleasant side effects

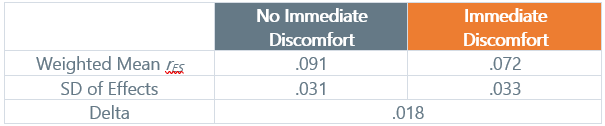

We hypothesized that behavior change associated with immediate discomfort would be harder to change compared with behavior change that did not have uncomfortable consequences. To explore this, we gathered coded effect sizes from published meta-analyses between 2004 and 2023 that reported specific effect sizes for distinct health behavior change effects (e.g., smoking cessation, exercise, diet change, vaccination, screening). We then coded each behavior on the basis of whether or not it would produce immediate discomfort or require significant immediate effort on the part of the patient. Our findings are summarized in Table 4 below. There is a modest effect in the expected direction. Though significant, we find it surprising that the effect would not be larger given how powerful these kinds of effects tend to be in many psychological studies.

Table 4. Modest Evidence for “Discomfort and Effort” Effects

- CONCLUSION 3: It is somewhat easier to make people change behavior through communication when the behavior does not come with an immediate price tag of pain, discomfort or effort.

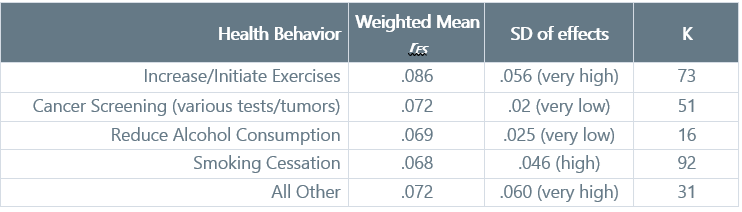

Taking the idea of effects of discomfort and effort a bit further, we might speculate that the effects of persuasive communications are a function of the distinct behaviors themselves. In other words, we can forget trying to “categorize” behaviors based on common characteristics, and simply look at persuasive effects on a behavior-by-behavior basis. After all, in principle, each distinct behavior comes with its own distinct “signature” of costs, effort, and reward. Extending our previous analysis (again, capturing reported effects from healthcare meta-analyses from 2004 to 2023), we looked at communication effects at the level of distinct health behaviors. Not surprisingly, the most common ones involve behaviors like exercise, smoking/alcohol reduction and cancer screening.

Table 5. Persuasive Communication Effects on Individual Health-Related Behaviors

We have included all of the source studies for these effects in our Reference list, and interested readers can contact us for our coded list of meta-analytic effects for individual health behaviors.

- CONCLUSION 4: On balance, persuasive communication appears to apply about equally well to all tested health-related behaviors

Taking all of these findings together, we are left with an interesting feeling of tension. Clearly, we know that persuasive campaigns are harder in some situations than in others. Yet, with the exception of the “subtraction effect,” most of the intrinsic characteristics of the behaviors that we are looking at don’t seem to be major factors in whether or not persuasive messaging works. It’s not that the effects we expect don’t exist at all. It’s just that they are small. So, what’s going on? The first clue is that the variance in the recorded effects for many of these behaviors is quite high. That means that communications worked much better or much worse on the same underlying behavior across studies. If those differences are not a function of the behaviors themselves, where do they come from? There are two obvious possibilities, and we will explore both of them in subsequent posts:

- POSSIBILITY #1: The effectiveness of persuasive communication is a function of characteristics of the communication content itself

- POSSIBILITY #2: The effectiveness of persuasive communication is a function of characteristics of the individual humans they are targeting

Take-Home Points

One thing that is abundantly clear from communication science is that we can have a major impact on behavior change, but we do need to go in with our eyes open as to the size of the challenge we may encounter in getting to that goal. Taken together, these findings are broadly encouraging for marketers.

- POINT #1: First, marketers can reasonably expect to have the ability to change a wide range of behaviors through persuasive campaigns – including very complex behaviors.

- POINT #2: Generally speaking, it will be easier to get customers to “add on” to their current habitual behaviors and preferences rather than replace them (i.e., subtract something from their endowment).

- POINT #3: Additionally, it is always worth thinking about what you are asking your customers to do in terms of the costs and rewards that they will experience if they make the change you are suggesting. You can expect modest headwinds against your messaging when you are asking people to do things that come with immediate “costs” in effort or discomfort.

Relevant Topic: Knowing that behaviors themselves are only modestly related to communication effectiveness, we have a series of posts which unpack other levers that marketers can pull to influence customers. Not surprisingly, this will take us into the exciting world of psychology. See posts titled “The Power of Tailoring to Customer Psychology“, “Leveraging Customer Psychology for Powerful Communications – Part 1: Communicating to Strengthen Self-Determination” and “Part 2: Fear as a Lever for Behavior Change“.

To learn more, contact us at info@euplexus.com.

About euPlexus

We are a team of life science insights veterans dedicated to amplifying life science marketing through evidence-based tools. One of our core values is to bring integrated, up-to-date perspectives on marketing-relevant science to our clients and the broader industry.

References

Armanasco, A. A., Miller, Y. D., Fjeldsoe, B. S., & Marshall, A. L. (2017). Preventive health behavior change text message interventions: a meta-analysis. American journal of preventive medicine, 52(3), 391-402.

Chapman, G. B. (2004). The psychology of medical decision making. Blackwell handbook of judgment and decision making, 585-603.

Golman, R., Hagmann, D., & Loewenstein, G. (2017). Information avoidance. Journal of economic literature, 55(1), 96-135.

Mullen, P. D., Mains, D. A., & Velez, R. (1992). A meta-analysis of controlled trials of cardiac patient education. Patient education and counseling, 19(2), 143-162.

Hubbeling, D. (2020). Rationing decisions and the endowment effect. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 113(3), 98-100.

Jaeger, C. B., Brosnan, S. F., Levin, D. T., & Jones, O. D. (2020). Predicting variation in endowment effect magnitudes. Evolution and Human Behavior, 41(3), 253-259.

Joyal-Desmarais, K., Scharmer, A. K., Madzelan, M. K., See, J. V., Rothman, A. J., & Snyder, M. (2022). Appealing to motivation to change attitudes, intentions, and behavior: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 702 experimental tests of the effects of motivational message matching on persuasion. Psychological Bulletin, 148(7-8), 465.

Kok, G., van den Borne, B., & Mullen, P. D. (1997). Effectiveness of health education and health promotion: meta-analyses of effect studies and determinants of effectiveness. Patient education and counseling, 30(1), 19-27.

Leue, A., & Beauducel, A. (2008). A meta-analysis of reinforcement sensitivity theory: On performance parameters in reinforcement tasks. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 12(4), 353-369.

Lustria, M. L. A., Noar, S. M., Cortese, J., Van Stee, S. K., Glueckauf, R. L., & Lee, J. (2013). A meta-analysis of web-delivered tailored health behavior change interventions. Journal of health communication, 18(9), 1039-1069.

Noar, S. M., Benac, C. N., & Harris, M. S. (2007). Does tailoring matter? Meta-analytic review of tailored print health behavior change interventions. Psychological bulletin, 133(4), 673.

Rodriguez Rocha, N. P., & Kim, H. (2019). eHealth interventions for fruit and vegetable intake: a meta-analysis of effectiveness. Health education & behavior, 46(6), 947-959.

Snyder, L. B., Hamilton, M. A., Mitchell, E. W., Kiwanuka-Tondo, J., Fleming-Milici, F., & Proctor, D. (2004). A meta-analysis of the effect of mediated health communication campaigns on behavior change in the United States. Journal of health communication, 9(S1), 71-96.