Table of Contents

- Quick Summary & Introduction

- Using Simple Print as a Benchmark

- How Much do we Buy with Rich Media?

- Creating an Immersive Environment

- “Just Text Me”

- The Power of Being in the Room

- Printed Communications are Fine, But Keep Them Short

- Take-Home Points

Quick Summary

In this installment, we examine the rich data that has accumulated over the last few decades on medium or channel effects in persuasive communication for healthcare. We examine the specific effects that can be achieved through different communication media when it comes to shaping downstream behavior. In addition, we provide some basic guidance to marketers for thinking about the value of the different components of their omnichannel strategy for product messaging.

Introduction

Our series of posts on messaging and persuasive communication focuses on giving marketers an evidence-based way of planning for and designing campaigns. On one hand, we have been trying to provide a way for marketers to set realistic expectations about what they can credibly achieve given the innate challenge associated with complex behavior change. On the other hand, we are also illuminating ways to maximize impact. This short post will focus on understanding the importance of the medium or channel that you select for your communications.

What kinds of medium effects might we expect to see?

Most of us would probably assume that more visually complex, stimulating and immersive web-based delivery will be far better than traditional printed materials. Another assumption might be that video-based messages are far more powerful because many people find visualization enhances learning. And perhaps the story gets more nuanced if we start considering things like cohort effects. Will older populations respond to different media? Additionally, just because video or web-based delivery is more engaging (or entertaining) doesn’t automatically mean it will be more persuasive. Further, isn’t there something to be said for traditional face-to-face communication, with its capacity for adaptation, tailoring, empathy and social pressure? As always, the best thing to do is look at the data to see if we can sort out some answers with evidence.

As we do this, we’re going to try to understand not just which one wins, but also by how much. The effort to quantify the distinctions between media channels is important because the differences in investment in creating and using different types of media are not trivial. Further, omnichannel promotion is here to stay, so thinking critically about where we are getting the most value out of our efforts to drive productive customer behavior change makes business sense.

For this post, we’ll focus on parsing the differences between:

- Traditional printed or text-centric communication

- Web-based communication (which we’ll try to parse in terms of its degree of “immersiveness”)

- Audio and video (as in streamed video)

- Human-to-human communication

- And the special topic of text messaging, which can be used as either its own intervention or as a way of reinforcing communications that have been delivered in other channels

As we examine these questions, we’ll be focused on studies that measure actual behavior change within healthcare. However, as we saw in our post called “Persuasive Messaging Can Shape Any Endpoint”, the data suggest that the trends reported here would carry over to influences on beliefs, attitudes and intentions as well.

Using Simple Print as a Benchmark

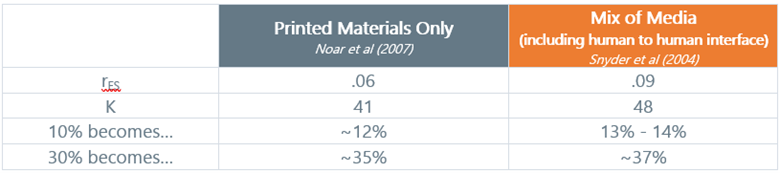

One powerful feature of the accumulated science on persuasive communication in healthcare is that we can now set realistic expectations for basic communication effects. From our perspective, the benchmark for comparison of any channel or medium should be based on simple print/text-based messaging that is trying to change actual behavior. In other words, it makes sense to start with the least expensive and simplest medium and see how it works on the most difficult-to-change endpoint (i.e., behavior change in healthcare). We know from several meta-analyses that the average effect size for this scenario is about rES = 0.5 to 0.7. We’ve referenced the wonderful meta-analysis by Noar et al from 2007 in several posts, and we will use it here as our benchmark effect size. Turning to the question of non-print media, an early meta-analysis by Snyder et al (2004) helps us anticipate what we might see. They make the qualitative point that in-person interventions such as face-to-face conversations with physicians produce larger behavior change results than what can be accomplished through mass-media communication. The Snyder et al article does not break its findings out by specific media channels, but clearly the moment we start examining non-print interventions, we already know our effects will be larger. Happily, subsequent research syntheses address specific channel and medium differences very directly.

Table 1. Benchmark Effect Sizes for Evaluating Channel Effects

How Much Do We Buy with Rich Media?

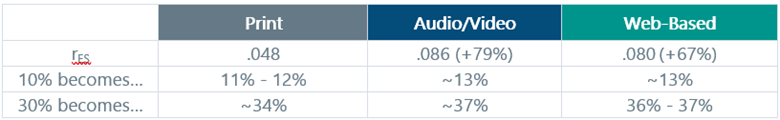

Two meta-analytic reviews provide the backbone answers to this question. First, Shen, Sheer and Li (2015) conducted a meta-analysis of persuasive communications using narrative-based content (e.g., personal anecdotes/stories) in persuasive communications about health behavior change, and part of their analysis focused on medium effects. They found that simple print-based messages were sharply less potent in shaping behavior change compared with video-based communications. Their print-based effect sizes are in line with those reported by Noar et al (see table above), and the rich overlay of video and audio stimuli predictably yield more behavior change. Another study focused exclusively on web-based communication interventions, again focusing exclusively on health behavior. This work by Webb et al (2010) involved a synthesis of 85 studies and over 40,000 human participants. They found that the average web-based behavior change intervention yielded an average effect size of 0.08. We will dig into different degrees of “immersive” experience in a moment, but at first pass it is worth noting that web-based and simple video-based communications have basically identical effects. As the authors note, most web-based interventions present the bulk of their ideas via videos, many of which will include the kind of anecdotal and narrative elements emphasized in the Shen et al (2015) studies. We can immediately see that moving to rich media is not a cure-all for behavior change, as the total impact on behavior is still more or less in line with the effects reported in the two reference meta-analyses. However, the incremental effect is in the neighborhood of 65% to 75%, which is impressive on a relative basis, particularly given that we marketing is often a game won by inches.

Table 2: Comparing the Impact of Messaging Delivered Through Different Media

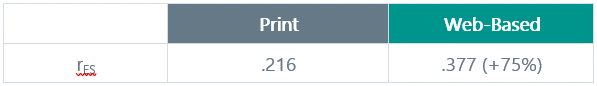

Before continuing our discussion of healthcare behavior effects, I want to take a quick trip to the world of consumer advertising. A meta-analysis by Ladeira et al (2022) looked at media effects on the establishment of brand familiarity (which is much easier to influence than either attitudes or behaviors – see our post entitled “How Many Message Exposures are Needed?”). Their analysis again suggests that web-based delivery is about 75% more effective than print. In other words, the transition from print to web-based communication has a virtually identical effect size increase as what we saw in the healthcare studies.

Table 3: Print vs Web-Based Communication Effects on Brand Familiarity

One reason to emphasize this similarity in effect is that it is far from unique. Thanks to the massive increase in empirical work on persuasive communication in marketing-relevant science, we’re starting to see these kinds of patterns that allow us to be much more precise in understanding how effective different types of communication tactics will be. Now back to our story…

Creating an Immersive Persuasive Environment

The Webb et al study points out that one of the key advantages of using a web-based delivery is that you can surround the core message with a range of supplemental and reinforcing experiences. Some of the supporting elements include:

- Text messages – which are used for a wide range of things from motivational priming to call-to-action reminders

- Access to consultants or content experts who can answer questions or provide assistance

- Peer-to-peer communication

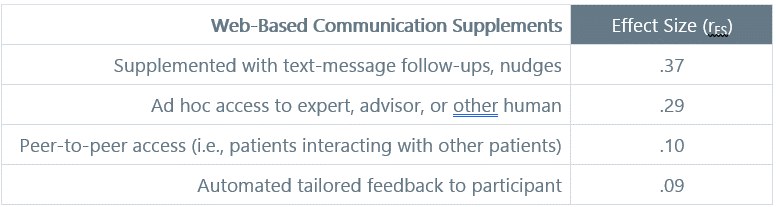

Webb et al isolated these effects wherever they had sufficient data to do so, and the results are engaging. As you read this table, the two benchmarks to keep in mind are the average print-material effect of .06 and the average web-based effect of .08. In broad strokes, we can see that adding different features to the environments where we deliver persuasive communication can have a very meaningful impact on how much behavior change we can expect. Readers may or may not be surprised to see that access to a human (either as an expert or advisor) has a potent effect, essentially tripling the effect size. Supplementing the initial communication with text-messaging follow-ups also has a whopping effect – so much that we want to unpack it a bit further. Overall, we are beginning to see the pattern that the richness and immersiveness of our communication efforts translate to rather dramatic improvements in our behavior change efforts.

Table 4: How Aspects of Web-Based Immersion Contribute to Persuasiveness of Health Messaging

“Just Text Me”

Readers might not be surprised that the text-messaging bolt-on effect got noticed. Since that meta-analysis, a huge number of individual trials have been conducted to study its effects on diverse types of behavior change, including exercise and drug adherence, in disease settings ranging from diabetes and cardiovascular medicine to neuroscience to oncology. We may do a separate summary of this literature in another post, but for concision, here are the main trends. Text-only interventions produce solid results.

- In two meta-analyses of text-only interventions on health behaviors (compared with controls), Armanasco et al (2017) found a solid effect of rES = .12, and Head et al (2013) found larger effects at rES = .16

- In a meta-analysis of text interventions on physical activity/exercise, Smith et al (2020) found similar effects of text-only and mixed modality interventions. They reported text-only effects of rES = .13. However, to further align with the work by Webb et al above, they also reported effects when the text messaging was used as a supplement to face-to-face communication, the effect rose to rES = .27.

- Finally, a meta-analysis of text-based drug adherence (Thakkar et al, 2016) showed a similar effect of rES = .20 when text-reminders were compared to controls. In our judgment, the Armanasco et al paper represents the most contemporary and generalized effect of text message-only effects because they were agnostic to disease setting. So, we recommend the rES of .12 as the benchmark for isolating the text message effects. However, it is possible that even larger effects can be achieved.

The Power of Being in the Room

While the cost of human-to-human communication may be regarded as prohibitive in many settings, it is worth understanding what we might be giving up if we completely abandon this channel. Not surprisingly (to the author at least), in-person delivery of persuasive messages carries a lot of punch in terms of delivering behavior change. A very early meta-analysis from Mullen et al (1998) explored this effect as part of an assessment of 74 studies examining different types of clinical behavior change resulting from educational or counseling interventions delivered in-person in various settings, including offices and clinics, patients’ homes and schools. Their mean effect size for in-person interventions was rES = .29, which is substantially larger than anything we have seen with other single medium effect. Note that the Mullen et al data are elaborated by subsequent work reported in Snyder et al (2004). When compared to traditional print communications, face-to-face persuasion is 4 to 5 times more potent in shaping behavior change.

Printed Communications are Fine, But Keep Them Short

The first thing we looked at in this summary was the value of print-based communication, and the effects have seemed increasingly modest as we’ve examined other channels. Nevertheless, there are plenty of circumstances where you aren’t going to be able to get someone to sit down and watch a video about your product, or talk to a person, or spend time on your website. Thus, an important related question has to do with what types of printed or text-based formats are most effective. The Noar et al (2007) meta-analysis provides the answer. They broke their findings out according to the length and format of the printed materials, and the results are summarized below.

Table 5: Persuasive Effects on Behavior by Density of Printed Mediums

Take-Home Points

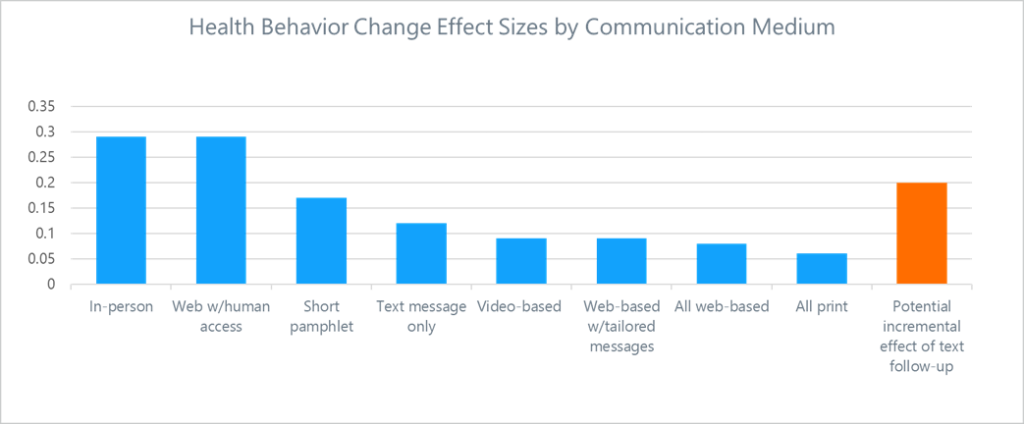

Because all the meta-analyses we’ve looked at included similar inclusion criteria and similar communication content, it is reasonable to summarize the effects we’ve seen across channels. The figure below shows the relative mean effect size for the isolated channels, as well as the incremental value of overlaying text message prompting/follow-up. For marketers trying to get a handle on how their omnichannel investments are likely to deliver on outcomes out in the real world, we hope this will provide a basis for estimation.

Figure 1: Health Behavior Change by Communication Medium

For marketers, we also suggest the following take-home points are worth keeping in mind.

- POINT #1: The 3:1 Heuristic for Human Interface

- As you would expect, the more human-based the communication channel is, the more effective it will be at changing behavior. You can use the rough ratio of 3:1 as a heuristic for estimating the behavior impact multiple that will come from human-to-human delivery compared to other major types communication channels/media.

- POINT #2: Moving from Print to Video/Web Buys You 75% More Potency

- Web-based communication, by itself, is no more effective than video-based messaging. So, a video about your brand placed on youtube may be just as good as a branded website, as long as people get exposed to it.

- POINT #3: Print Can Still Stick the Landing

- Don’t assume that print-based communications will not have an impact, because they will. As with all communications the more laser-focused they can be on the specific behavior change and why it matters, the more effective it will be. As for those leave-behind pamphlets you build for physician waiting rooms? They work!

- POINT #4: Text Messaging is a Level-Up

- Text messaging seems to give a super-boost to messaging when it comes to behavior change. For some contexts they may be awkward or inappropriate, but wherever you have a customer already engaging with your messages in some other context, you are likely to get substantial incremental lift from using them as follow-ups or reminders. That lift appears to generalize well across types of behavior and disease setting.

Relevant Topic: As we continue to synthesize major trends in the science of persuasive communication and messaging, we want to continue to expand on the topic of how to plan more thoughtfully for campaign development. In our post titled “Are Some Health Behaviors Harder to Shape With Marketing?“, we take a look at the important question of whether some kinds of healthcare behaviors are simply harder to change through marketing efforts. The answers may surprise you.

To learn more, contact us at info@euplexus.com.

About euPlexus

We are a team of life science insights veterans dedicated to amplifying life science marketing through evidence-based tools. One of our core values is to bring integrated, up-to-date perspectives on marketing-relevant science to our clients and the broader industry.

References

Armanasco, A. A., Miller, Y. D., Fjeldsoe, B. S., & Marshall, A. L. (2017). Preventive health behavior change text message interventions: a meta-analysis. American journal of preventive medicine, 52(3), 391-402.

Head, K. J., Noar, S. M., Iannarino, N. T., & Harrington, N. G. (2013). Efficacy of text messaging-based interventions for health promotion: a meta-analysis. Social science & medicine, 97, 41-48.

Junior Ladeira, W., Santiago, J. K., de Oliveira Santini, F., & Costa Pinto, D. (2022). Impact of brand familiarity on attitude formation: insights and generalizations from a meta-analysis. Journal of Product & Brand Management, 31(8), 1168-1179.

Mullen, P. D., Simons-Morton, D. G., Ramírez, G., Frankowski, R. F., Green, L. W., & Mains, D. A. (1998). A meta-analysis of trials evaluating patient education and counseling for three groups of preventive health behaviors. ACP JOURNAL CLUB, 128, 68-68.

Noar, S. M., Benac, C. N., & Harris, M. S. (2007). Does tailoring matter? Meta-analytic review of tailored print health behavior change interventions. Psychological bulletin, 133(4), 673.

Shen, F., Sheer, V. C., & Li, R. (2015). Impact of narratives on persuasion in health communication: A meta-analysis. Journal of advertising, 44(2), 105-113.

Smith, D. M., Duque, L., Huffman, J. C., Healy, B. C., & Celano, C. M. (2020). Text message interventions for physical activity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. American journal of preventive medicine, 58(1), 142-151.

Snyder, L. B., Hamilton, M. A., Mitchell, E. W., Kiwanuka-Tondo, J., Fleming-Milici, F., & Proctor, D. (2004). A meta-analysis of the effect of mediated health communication campaigns on behavior change in the United States. Journal of health communication, 9(S1), 71-96.

Thakkar, J., Kurup, R., Laba, T. L., Santo, K., Thiagalingam, A., Rodgers, A., … & Chow, C. K. (2016). Mobile telephone text messaging for medication adherence in chronic disease: a meta-analysis. JAMA internal medicine, 176(3), 340-349.

Webb, T., Joseph, J., Yardley, L., & Michie, S. (2010). Using the internet to promote health behavior change: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the impact of theoretical basis, use of behavior change techniques, and mode of delivery on efficacy. Journal of medical Internet research, 12(1), e1376.