Table of Contents

- Why We Care About Message Repetition

- Message Repetition & Behavior Change in Healthcare

- Estimating the Incremental Value of Each Additional Message Exposure

- Shaping Recall, Attitudes & Content Retention Through Repetition

- Too Much of a Good Thing

- Implications for Marketers & Insights Professionals

Why We Care About Message Repetition

Marketers naturally want to know how many times they have to get their messages/ads in front of customers to achieve a maximum effect. From our own experience with content learning (e.g., from classroom exposure or textbooks) and with seeing advertisements in our day-to-day lives, most people assume that repetition plays a role in driving the effects that marketers are looking for, which would include:

- Aided Recall/Awareness (i.e., basic recall, as in, “do you remember seeing an ad for…?”)

- Retention (being able to reference specific content from an ad/message)

- Attitude toward a product/organization

- Behavior change

It can be challenging to guess precisely how repetition of exposure would shape each of these outcomes, partly because personal experience gives us multiple, conflicting intuitions. For example, many of us will recall seeing a particular ad for a product for the first time and making an instant decision to buy it. We may also recall cases where our feeling about a brand became more favorable over time as we got familiar with it through an amusing advertisement. And to round things out, we might also remember times when we gradually moved from liking a brand to liking it less as we got exposed to more of its advertisements over time. Until recently, perspective and evidence from academic research did not offer much clarity on the value of message repetition, as both theoretical models and data often seemed to conflict.

The data on this topic can be a bit complicated, so we are going to start by focusing on the most concrete findings concerning message repetition as it relates to driving actual changes in behavior. Then we’ll dig into the nuances of shaping endpoints that are upstream of actual behavior change.

Message Repetition & Behavior Change in Healthcare

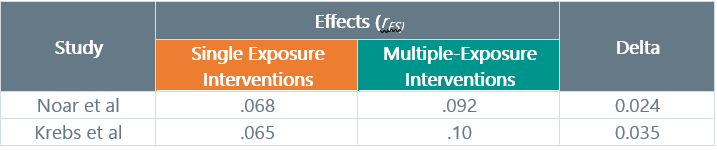

To begin, various meta-analytic sources confirm what we would all assume: Getting a customer exposed to an ad/message on multiple occasions creates a larger downstream effect on behavior compared to just a single exposure. The first study we’ll examine was a meta-analysis by Noar et al (2007), which quantified single-vs. multiple-exposure communications related to a range of healthcare behaviors, including smoking cessation, drug adherence, and vaccination. Their synthesis of effects from fifty-seven published experiments found that the effect size delta between single-exposure vs multiple-exposure studies was equal to 0.024. This effect is shown in Table 1 below. The delta in effect size (rES) for additional exposures is not trivial, accounting for ~35% of the first-exposure impact on behavior. Clearly the relative value of incremental exposures diminishes compared to the power of the initial exposure, but that’s what we would expect.

Estimating the Incremental Value of Each Additional Message Exposure

So, the question is: How much impact do I buy for each additional exposure? Unfortunately, Noar et al do not parse this estimate. However, a subsequent meta-analysis by Krebs et al (2010) looked at web-based message exposures and coded for substantial variation in the number of “touch points” used in the message intervention. So, like Noar et al, they coded studies that included just a single exposure and compared those with studies that uses >1 exposure. These analyses show impressive congruence in effect sizes reinforcing the degree of accuracy that can now be achieved in the scientific study of message effects.

Table 1. Net Effects of Single vs. Multiple-Exposure Communications Studies in Healthcare

The Krebs et al study reports an average increase in total behavior change effect size (reported as Cohen’s g and converted to rES here for consistency) of 0.01 for each repeated exposure, or about 8% of the value of the single-exposure condition on average. Obviously, we would expect variation on the basis of the quality of the content, the baseline level of behavior that exists in the market before the campaign launches, and the total number of exposures. But, for planning purposes, we think this is a useful heuristic. To bring this to life, let’s convert these effects into our “bodies moved” index, where we estimate how much change we can drive relative to some behavioral baseline. I encourage readers not to be dismayed by these findings. Remember, the studies in question are focused on changing some of the most intractable behavior challenges we know of. Most of your marketing efforts will be focusing on more malleable targets.

Table 2. A Practical View on Incremental Exposure Value

If you have a marketing goal of moving a baseline behavior from a starting value of 30% to an ending value of 50%, the combination of the Noar et al and Krebs et al findings above should help you with that process.

Shaping Recall, Attitudes & Content Retention Through Repetition

As we will be discussing in future posts, marketers are often interested in shaping customers in a way that is “upstream” of behavior. Depending upon where we are in a brand life cycle, we may be more concerned about driving basic disease and brand awareness, specific beliefs about the product and shaping attitudes. It turns out that the use of repetitive communication to shape these endpoints has its own complexities. To get a handle on what to expect, we summarize learnings from several major statistical integrations of published experiments. First, Schmidt and Eisend’s 2015 meta-analysis from the Journal of Advertising makes an enormous contribution to our understanding of these dynamics and represents yet another illustration of the “big data”-style power that has evolved from the explosion of marketing-relevant science. Their work centers exclusively on advertising exposures and can summarized in two key take-aways.

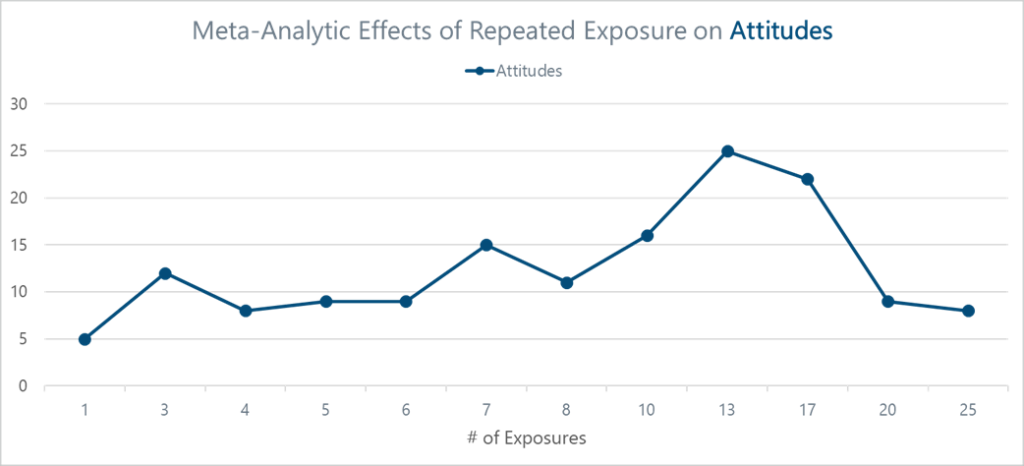

Key Take-Away #1: Impact on Attitudes

First of all, attitudes can be challenging to influence, particularly if people already have strong feelings about a product or condition before seeing your message. However, with repeated exposure, attitudes toward a product move fairly predictably through an inverted U-shaped curve as we expose customers to messages about the brand. To put this more plainly, as we expose customers to messages, positive attitudes toward a product increase fairly linearly for the first number of exposures, then plateaus and then declines. This effect is cross-validated in a 2017 meta-analysis by Montoya et al, which we discuss in a moment. The Schmidt and Eisend analysis also shows that the optimal number of exposures is ten, beyond which, attitudinal effects begin to trend downward. I encourage readers to think about their own experiences with seeing clever or useful ads. Was there a point in your exposure to the ad where you began to dislike it or wish it would stop playing so much on your news feed?

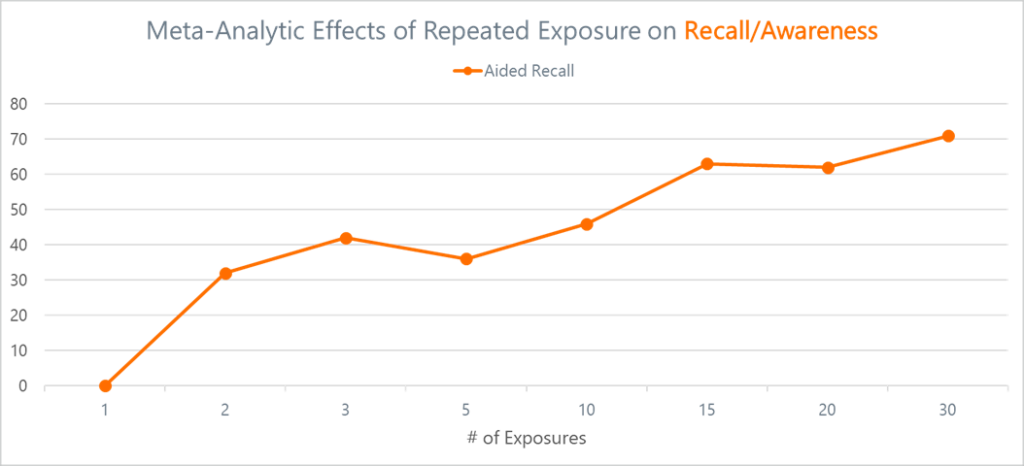

Key Take-Away #2: Impact on Recall/Awareness

Not surprisingly, recall works differently than attitudes do because it lacks the overlay of emotionality. As the number of exposures to the communication increases, recall increases more or less linearly, and it does not display the eventual decline effects seen with attitudes. Recall also requires more tightly clustered exposures, which contrasts with attitude-shaping. So, if the goal is to get people to simply be familiar with the product, you can hit them as often as you like and make sure they continue to get exposed. We think this recommendation is especially salient when marketers are doing pre-commercial market development for diseases or disease mechanisms.

These effects are cross-validated in another meta-analysis by Montoya et al (2017), which looks at a much broader array of stimulus types used in psychology and cognitive science research, rather than strictly focusing on ad concepts/messages. However, we believe that it is sufficiently marketing adjacent to be worth including in this discussion. These authors also examine the effect of repeated exposure on multiple endpoints: (1) attitudes (liking), (2) aided recall/awareness and (3) retention (i.e., ability to play back specific information from the communication). This analysis captures measures on the dependent variables above for any reported number of exposures within the published experiments that were synthesized. In the two figures below, we show a modified view of their complete data set, focusing on the most commonly referenced time points from this meta-analysis. This reduces the “noise” in the data and clarifies the shape of the exposure frequency-outcome relationship. The effect values are reframed as changes from the first exposure, rather than absolute values and they are standardized to reflect a common scale to make comparison easier. The basic effects observed are:

- Recall/Awareness: This endpoint appears to increase more or less linearly, as Schmidt and Eisend suggest it should.

- Attitudes: Also consistent with Schmidt and Eisend’s findings, the Montoya et al study shows that attitudes have an inverted-U shaped response to repeated exposure. In Figure 2, we see that the saturation point appears to occur around the 13th exposure, rather than the 10th exposure reported in the earlier study. However, for practical purposes, we are not sure that this matters all that much.

Figure 1: Changes in Aided Recall/Awareness Across Repeated Exposures

Overall, this more expansive study aligns nicely with the Schmidt and Eisend analysis, giving us increased confidence that these relationships are both real and reliable, as well as applicable to numerous settings.

Figure 2: Changes in Attitude Toward Stimulus Target Across Repeated Exposures

Why are the relationships so “bumpy”? Readers may be wondering why the shape of the frequency-outcome functions are not smoother. To some extent this is just the nature of field-based research; however, we have included a methodological footnote that sheds additional light on the lack of smoothness in these relationships.

Too Much of a Good Thing

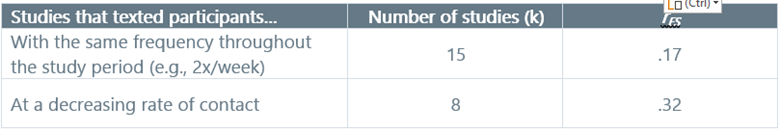

To round out this discussion, we want to share some insights from two other studies that shed light on the topic of frequency effects from different points of view. The first is a 2017 study that meta-analyzed the use of text-messaging interventions in shaping health behaviors (Amanesco et al , 2017). As is so often the case, many of these behaviors include intractable challenges such as smoking cessation and safe sex practices. The specific finding we want to highlight has to do with the density of text-based communications that the study participants received. As explained in Table 3 below, the text interventions were more effective at shaping behavior when the study design gradually decreased the number of messages that participants received. In other words, they got more messages at the beginning and then received fewer as time went on. By comparison, other studies used a consistent frequency of text delivery. The “decreasing” approach had approximately twice the total effect on behavior change.

Table 3. The Impact of Text-Based Communications on Health-Related Behaviors

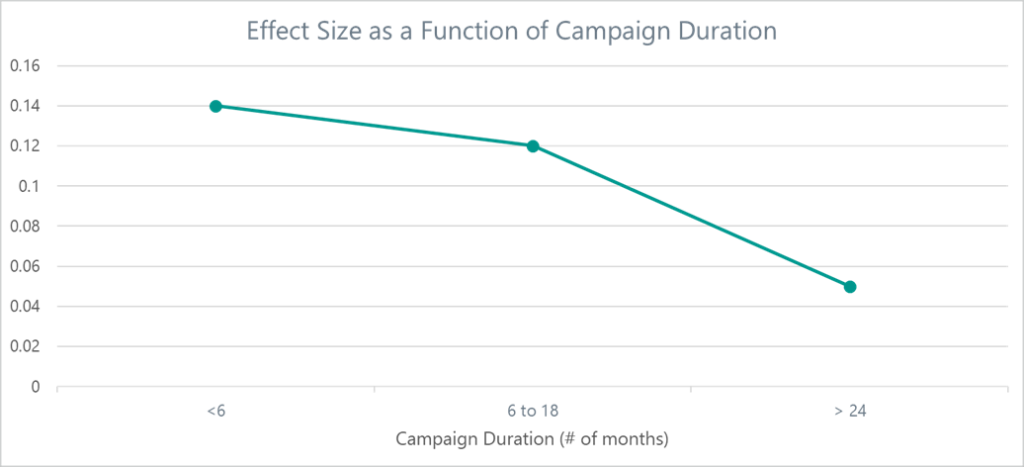

A much earlier meta-analysis conducted by Snyder & Hamilton (2004) took an interesting angle on persuasive messages in healthcare settings. Their analysis reflects 48 behavior change campaigns and included almost 170,000 humans. Although this paper is missing a large number of more contemporary studies, it still offers an important lesson. They found that the net effect on behavior change from persuasive health communications was sharply higher for campaigns that were shorter, with effect sizes deteriorating for those campaigns that extended beyond six months. The correlation between campaign length and effect size was reported at r=-0.50.

Figure 3. Saturation Effects from Extended Communication Campaigns in Healthcare

I think it is reasonable to assume that, by definition, the average number of exposures in longer communication campaigns is higher.

Both of these studies seem to point to the need for consideration of oversaturation of communication exposure. In a sense, limited advertising budgets may place natural guardrails around the tendency to over-communicate with customers. Even so, we believe these findings, along with the earlier analysis of attitudes (and their inverted-U-shaped response curve) suggest the need for some sensitivity about when specific messages have overstayed their welcome.

Implications for Marketers & Insights Professionals

It is no surprise that repeated exposure to your messages buys you more of what you are trying to accomplish, whether that is driving awareness and familiarity, shaping how customers feel about your product (attitudes) or changing behaviors. In planning for campaign investment, here are four useful points to keep in mind.

- POINT #1: FIRST EXPOSURE WILL GIVE YOU MOST VALUE

- Whether you are shaping beliefs, feelings, recall or behavior change, your first exposure buys you the most value. The incremental value of each additional exposure is small but non-trivial. And since messaging is a game of winning by inches, it is worth understanding that you can expect each additional touchpoint to buy only a modest incremental value compared with your first exposure effect.

- POINT #2: IF THE GOAL IS AWARENESS, KEEP MESSAGING!

- Some campaigns are focused on getting customers to simply know that something exists – for example, disease awareness or disease definition campaigns. For this purpose, the accumulated data indicate more communication leads to better outcomes.

- POINT #3: WATCH OUT: ATTITUDES WILL PEAK AT SOME POINT

- If we are trying to influence how customers feel about a brand, we need to watch out for the saturation point beyond which their attitudes are likely to deteriorate. That switch will begin to happen somewhere in the neighborhood of 10 to 15 exposures.

- POINT #4: OVER-SATURATION IS OBVIOUSLY A THING

- Lastly, virtually everything that we have examined here is pointing to the reality that, when it comes to persuasive communication, sometimes too much is really too much. We need to balance the incremental cost of communications against the effects we are likely to obtain. And we need to keep an eye on where we are in the communication life cycle.

Related Topic: The most basic question about campaign effects that we’ve tried to answer in various ways is: How much behavior change do you get? But another essential question marketers want to answer is: How long does behavior change last? We cover this question about the durability of communication effects in “Can Messaging Produce Durable Changes in Behavior“.

To learn more, contact us at info@euplexus.com.

About euPlexus

We are a team of life science insights veterans dedicated to amplifying life science marketing through evidence-based tools. One of our core values is to bring integrated, up-to-date perspectives on marketing-relevant science to our clients and the broader industry.

Methodological Footnote

The Montoya et al meta-analysis collects data from numerous studies and integrates them via meta-analysis. All the individual studies use repeated stimulus exposure and examine the endpoints (attitudes and recall, or what the authors describe as “familiarity”) at each point of exposure. The challenge for the meta-analysis is that not every study reports data for each exposure. As such, for each reported exposure in the Montoya et al analysis, the number contributing data points varies. This contributes to the “wobbliness” of the data that we see. Additionally, it is important to remember that, in real science, relationships between variables are almost never smooth and clean. Some noisiness is expected due to sampling and measurement error, among other factors.

References

Armanasco, A. A., Miller, Y. D., Fjeldsoe, B. S., & Marshall, A. L. (2017). Preventive health behavior change text message interventions: a meta-analysis. American journal of preventive medicine, 52(3), 391-402.

Krebs, P., Prochaska, J. O., & Rossi, J. S. (2010). A meta-analysis of computer-tailored interventions for health behavior change. Preventive medicine, 51(3-4), 214-221.

Montoya, R. M., Horton, R. S., Vevea, J. L., Citkowicz, M., & Lauber, E. A. (2017). A re-examination of the mere exposure effect: The influence of repeated exposure on recognition, familiarity, and liking. Psychological bulletin, 143(5), 459.

Noar, S. M., Benac, C. N., & Harris, M. S. (2007). Does tailoring matter? Meta-analytic review of tailored print health behavior change interventions. Psychological bulletin, 133(4), 673.

Schmidt, S., & Eisend, M. (2015). Advertising repetition: A meta-analysis on effective frequency in advertising. Journal of Advertising, 44(4), 415-428.

Snyder, L. B., & Hamilton, M. A. (2002). A meta-analysis of US health campaign effects on behavior: Emphasize enforcement, exposure, and new information, and beware the secular trend. Public health communication, 373-400.